Published in: World Archaeology 2017, vol 49, issue 4, pp. 526-546 doi: 10.1080/00438243.2017.1341331

Author: Zoran Čučković

Abstract: More than 1,000 Bronze and Iron Age hillforts can be listed for the eastern Adriatic region. These constructions left a mark on the landscape which is still perceptible today. In some cases, such as the island of Lošinj, this density is challenging to explain: almost thirty hillfort (or simply hilltop) sites were recorded on a rugged island with an area of 74km2. Different factors potentially involved in the formation of this settlement pattern are discussed (territorial control, surveillance, control of maritime networks), only to show that without considering some kind of symbolic display a plausible explanatory model cannot be devised. A new reading of the coastal seascape is proposed, inspired in part by costly signalling theory. Hillfort construction is interpreted as a discursive practice geared towards assertive display in front of potential seafarers.

Keywords: Bronze Age, seascape, costly signalling, hillforts, visibility analysis

Introduction

The expense invested in a message, especially when intended to communicate social or economic status of an individual or a community, seems an ideal guarantee of [its] trustworthiness. Nothing would prove better my standing than the capacity to dispose of wealth, time or energy in a seemingly offhanded manner. Such are the tenets, in a nutshell, of costly signalling theory (Bliege Bird and Smith 2005; McGuire and Hildebrandt 2005, Plourde 2008). The same line of argument has been developed in evolutionary theory: apparently wasteful behaviour, such as the high jumping of a gazelle in front of a predator, would signal its physical fitness (Plourde 2008). The problem of wastefulness or otherwise inexplicable cost of certain social practices is a puzzle that intrigued theorists such as Thorstein Veblen (2007 [1899]), Marcel Mauss (2007 [1925]) and Pierre Bourdieu (1979). In spite of their quite different approaches as well as diverse intellectual backgrounds, these authors converge on the idea that wastefulness – as in unnecessary consumption, overgenerous gift giving, artistic elaboration or costly architecture – has to be understood within the wider framework of social relations. It is through this framework that costly signals acquire their meaning and justification.

The costly signalling theory can be very helpful for understanding archaeological landscapes, in particular those dominated by massive and durable constructions such as large funerary or ritual monuments, fortifications or other imposing structures. Such landscape features are often difficult to explain in purely functional terms and betray “wasteful” behaviours. Constructed landmarks or other massive interventions in the landscape may fulfil such diverse functions as marking identities (Nora 1984), materializing ideologies (DeMarrais et al. 1996), signalling political authority (Glatz and Plourde 2011), or demonstrating competitive fitness (Neiman 1997). Most archaeological approaches dealing with such ideational landscapes (sensu Knapp and Ashmore 1999) are explicitly concerned with their communicative aspect, i.e. their propensity to convey messages to a wider audience.

Hillforts, fortified hilltop settlements dating from various prehistoric and historic periods and found across the globe, from New Zealand to Western Europe, pose some potentially fruitful challenges for the costly signalling perspective. In general, a defensive structure would preferably display a clear signal of its structural stability as well as of the vitality of the protected community (Trigger 1990, 122). Ideally, an attacker would be dissuaded by the very appearance of a stronghold. Moreover, hillforts often assume the role of cultural or territorial landmarks. A good example is Monte Cimino hillfort in Tuscany, a walled Late Bronze Age settlement perched on a peak 1050 metres above sea level, the highest point of Tuscia (Southern Etruria: Barbaro et al. 2013). The site was also a place for ritual activity and would have entertained “a political and ritual role in territorial organisation” (idem, 17).

On the island of Lošinj (Kvarner bay, Croatia: Figure 1), which will be examined here together with the adjacent island of Cres, such fortified sites combine to form a peculiar ‘fortified seascape’. Some 30 prehistoric hilltop sites, normally enclosed by drystone structures, are known for the island’s total surface area of 74 km2, which leaves less than 3 km2 of exclusive space per site. Even when taking into account all uncertainties regarding their number and location, the island remains remarkably endowed with sites that are commonly referred to as hillforts (cf. discussion below). Regarding possible environmental and geographical assets for such a development, it will be shown that the most plausible one is the key position of the island for maritime travel along the eastern Adriatic coast. When viewed from the sea, the island’s stony crest would have appeared as crowned with a multitude of enclosed sites, a massive statement on human occupation. Hillforts can, thus, be understood as costly signals directed to the island’s seascape.

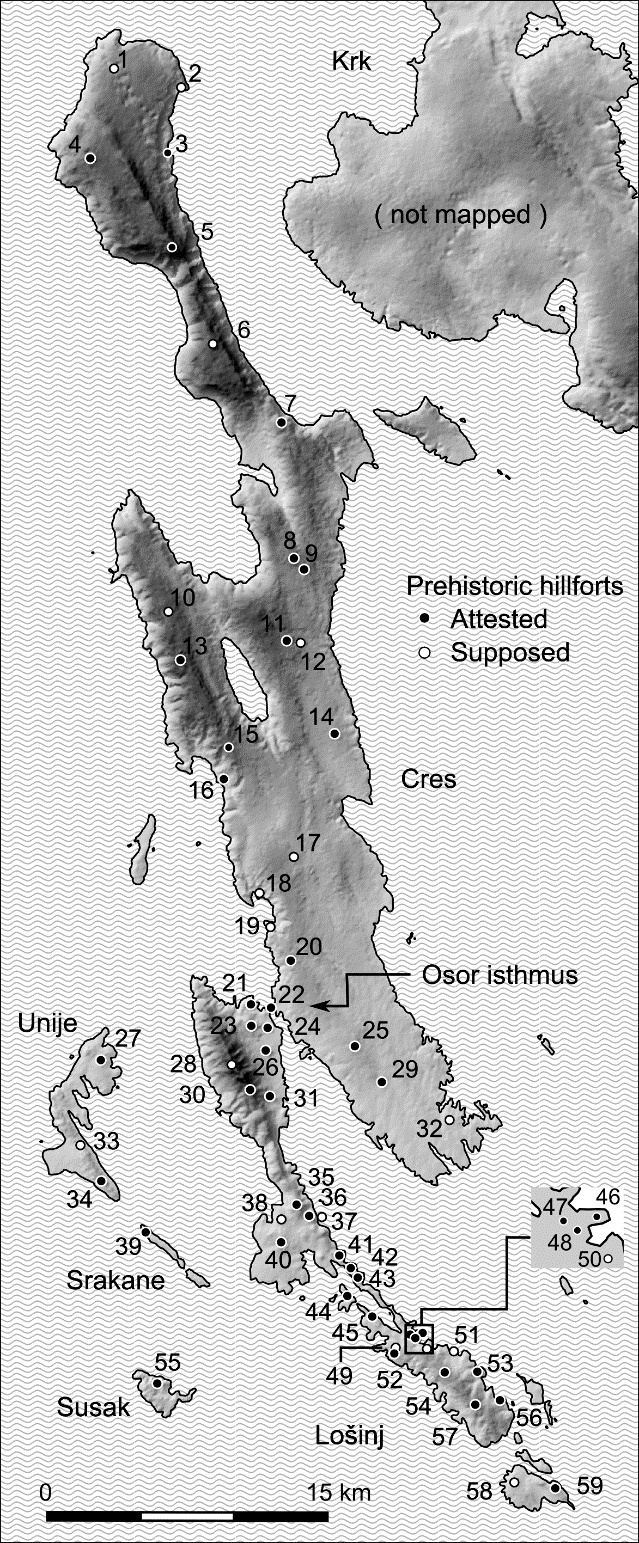

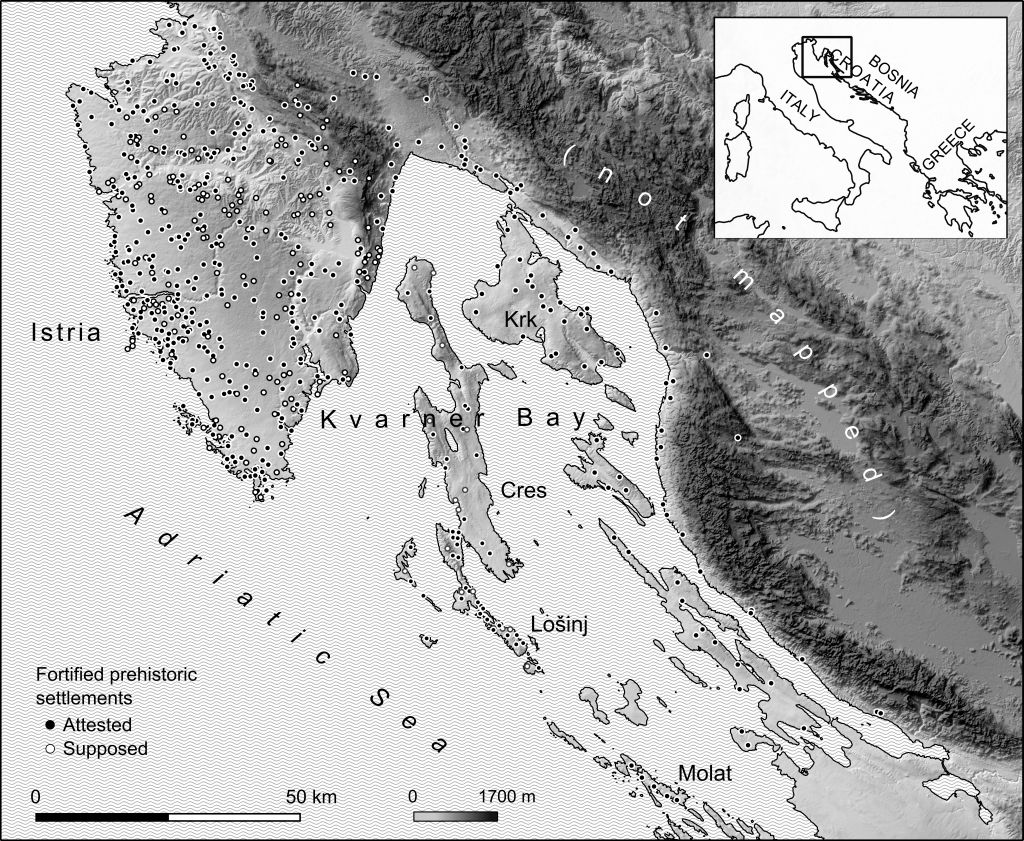

Figure 1. The region of Istria and Kvarner with places mentioned in the text. Prehistoric hillforts (Bronze and Iron Age) are mapped after Marchesetti (1903; 1924), Mirosavljević (1974), Batović (1977) and Buršić-Matijašić (2007). These publications with diverse levels of exhaustiveness and precision cannot be used as indicator of site distribution patterns – the map only illustrates a general hillfort density in the region. Elevation data: EU DEM.

The visual appearance of Cres and Lošinj hillforts in the surrounding seascape will be analysed using viewshed algorithm, a standard feature of most GIS packages. Prehistoric hillforts are regularly examined by this approach, whether to verify their potential for surveillance and visual control, or to assess their imposing visual appearance for local observers (Bell and Lock 2000; Ruestes 2008; Mlekuž and Črešnar 2014). In their study of south-eastern English hillforts, Hamilton and Manley (2001) consider that ‘hillforts provide a defined location from which to view the “world”’ (idem, 10) and, conversely, that a number of hillforts ‘function best when being “looked at”’ (idem, 31). Hillforts, thus, participated in shaping past worldviews – complex webs of meaning that permeate human thoughts and actions. Now, it has to be understood that modelling visual impact of archaeological sites can, at best, only serve to provide a glimpse into such frames of understanding (cf. Llobera 2012). However, this deficiency is shared across most archaeological sources, in particular for prehistoric periods: the success of visibility analysis resides in its integration with other archaeological findings, rather than in methodological minutiae.

From signals to discourse

To consider hillforts of a small island as a product of assertive communication implies extending the costly signalling theory to the entire settlement pattern, which thus becomes a discursive network. On a general level, the content of such discourse may be understood as some kind of identity affirmation in a sense that it communicates human occupation of the island. The costly signalling theory, therefore, needs to be combined with an analysis of concepts and values through which human landscapes are constituted. Furthermore, besides advertising territories, identities or economic fitness of their occupants, as if accomplished facts existing outside the discourse, costly landmarks or costly landscapes play an important role in the elaboration and materialisation of these very concepts (territory, identity, wealth, etc.: DeMarrais et al. 1996). This raises some important implications that need to be briefly exposed.

If anything, different strands of thinking that develop upon the idea of costly signals share a common drive to relate seemingly non-rational, wasteful behaviour to a functional explanation. Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic capital is revealing: the “symbolic” part does not refer to a theoretical, imaginary value, nor to the problem of inconvertibility into “real”, material capital; it rather denotes the crucial ingredient of social perception, or more generally, cultural ontology through which wealth, status or attractiveness are defined and negotiated (Bourdieu 1994, 160-161). The “economical” part of his definition refers to self-interested, rational or not, uses of symbolic capital by social agents in their perennial quest for distinction and ambition to stand out from their peers (Bourdieu 1979). Seemingly irrational expenditure of time or resources, for instance through consumption of goods or artistic and educational perfection, can have a certain logic in terms of establishing such differences (cf. Veblen 2007). Now, such thinking has been accused of reductionism: the symbolic domain is translated into some kind of delayed functionality, be it in terms of payoff time or in terms of social mechanisms which ultimately connect the symbolic realm with economy (Caillé 2005). But that may not be the main problem for archaeology.

Costly signalling theory, inspired by the notion of symbolic capital, has been developed as a subsidiary theory for behaviours that do not comply with expected, energy efficient modes (Trigger 1990; Bliege Bird and Smith 2005, McGuire and Hilderbrant 2005). It thus continues to reproduce the dichotomy between functional and symbolic domains, a major problem in archaeological interpretation (Bradley 2005). Typical subjects are practices that clearly betray high symbolic charge, such as construction of monuments (Neiman 1997; Glatz and Plurde 2011; De Souza et al. 2016), deliberate destruction of wealth (Bradley 1982) and artistic elaboration (Hodgson 2017, this volume). Hillforts, however, inextricably combine the symbolic with the functional, just as any human settlement for that matter. We would need, then, to combine these artificially opposed lines of interpretation, such as defence vs. symbolic display. Signals, visual or other, are an integral part of the process of settling down in a particular territory and their messages fortify territorial claims just as solid structures do.

Another problem, emanating from the angle of landscape archaeology, is the multiplicity of diverse visual or other signals in the landscape and their potential combination into a meaningful whole. Clearly, human communication cannot be analysed on the level of individual statements, and the same is valid for patterns that can be observed geographically. Discussions of costly signalling from an evolutionary standpoint are more often than not concerned with competitive, individualistic behaviours (McGuire and Hildebrandt 2005; Plourde 2008), but when dealing with human culture costly signalling has to be understood within specific cultural frameworks that define what would be an acceptable display of power, social status or economic fitness, and in which circumstances. That is, such practices tend to respond to a predefined scheme – a code – thus typically contributing to its strengthening and combining into a meaningful ensemble. Neiman (1997), for instance, discussed the phenomenon of standardisation regarding Mesoamerican ceremonial architecture. Note how these structures, by virtue of their similarity, combine into a meaningful network of shared references. Thus, the question is raised as to the relationship between individual signalling events and overarching social configurations, including landscapes.

From the historical perspective, in particular regarding the prehistoric hillforts, the following question arises: how could “costly landscapes” or costly discourse in general develop when neither a central authority nor a particular underlying scheme (a “masterplan”) could have existed? Considering long term developments, typically studied by archaeologists, the evolutionary perspective is, indeed, promising (notwithstanding charges of reductionism and teleology: O’Grady 1984; Johnson, 2011). For instance, the problem of standardisation of costly signals is related to the general issue of the development and evolution of discursive networks such as language, gift giving or any codified communication. B. Latour has called attention to the phenomenon of standardisation as fundamental for establishment of social relations across large groups of people (2005, 227ff.). However, such line of thinking may soon run into a dilemma when considering what best defines a suitable cost: could it be its position in the discursive network, specifically regarding the sequence of preceding “costly events”, or an amount of energy/time/wealth spent? Indeed, the expenditure of energy should normally follow established codes in order to convey a clear message; it should be integrated into pre-existing discourse. It is crucial here to understand that the concept of discursivity is distinct from the one of cultural embeddedness (even if closely related): it specifically addresses the autonomous evolution of discourse by its proper means (Foucault 1969). For instance, one could think of competitive production of ever more impressive costly events, without this necessarily bearing a direct relationship to economic sustainability or particular ideological underpinnings.

To be sure, the mentioned problems concerning costly signalling theory – namely, the transcendence of symbolic-functional dichotomy, cultural embeddedness, discursivity and historical contingency – are general in nature and cannot be addressed as such. They should, nevertheless, inform archaeological adaptations of the theory, lest archaeologists reproduce rather simplistic and mechanical evolutionary models.

Adriatic Bronze Age hillforts

Hillforts are the hallmark of the East Adriatic Bronze Age (approx. 2200 BC – 900 BC). Hilltop settlements are also known from earlier periods, but the density of Bronze and subsequent Iron Age hillforts is unprecedented: distances between neighbouring sites are mostly in a range of 2 or 3 kilometres (Figure 1; Batović 1977; Benac 1985; Buršić-Matijašić 2007). Such hillfort landscapes were, in most of the Adriatic zone, accompanied by burial mounds (Govedarica 1989; Mihovilić et al. 2011). In Istria, drystone ramparts of hillforts were equally used for burial (Hänsel et al. 2009). Finally, Bronze Age landscapes must have featured extensive drystone constructions such as field boundaries and various pastoral facilities, but these still remain poorly documented (Chapman et al. 1987, Sirovica 2015).

There is much regional variability in hillfort sizes and plans, perhaps the only unifying factor being the karstic terrain of the Eastern Adriatic zone which abounds in diverse landforms that are suitable for fortification or enclosure. In the region of Istria these sites date predominantly to the Bronze Age, while in the Iron Age the population seems to have been concentrated in fewer hillforts (Cardarelli 1983). The best known site is Monkodonja on the western coast of Istria, covering 3 ha, enclosed by massive drystone ramparts and settled from the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC until approx. 1200 BC (Hänsel et al. 2016). However, Monkodonja belongs to a group of large, densely settled sites: most of Istrian sites are smaller (1 to 2 ha) and were probably occupied with less continuity.

cca 2200 BC | Early Bronze Age |

1600 BC | Middle Bronze Age |

1200 BC | Late Bronze Age / Istrian Iron Age |

900 BC | Iron Age |

177 BC | Roman period in Istria |

Table 1 Simplified regional chronology

In general, there is little doubt that the massive increase of hillfort construction activity began in the Early to Middle Bronze Age in most of the East Adriatic zone (Cardarelli 1983; Benac 1985; Čović 1989). Unfortunately, the lack of detailed regional studies does not enable distinguishing detailed variations in chronological patterns over this large area. A rare exception is the research undertaken by Bosnian archaeologists in the 1970’s on some hundred hillforts in a mountainous region 50 to 70 kilometres inland from the coast. 21 sites were excavated by trial trenches and produced evidence for the first wave of hillfort construction in the Early Bronze Age, followed by a second wave dated to the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, while the Middle Bronze Age was mostly absent (Govedarica 1982; Benac 1985). A number of sites were also newly established in the 6th or 5th c. BC. However, the area in question has a mountainous climate which contrasts markedly to the Mediterranean zone, and may have had a different cultural evolution compared to coastal areas.

Possible uses and functions of hillforts in the overall settlement system are difficult to deduce, although most archaeologists would agree that they could not all have been central places or otherwise high rank, permanently inhabited settlements. A. Benac speculates that only a third or so of some hundred sites studied in the SW Bosnia would have been permanently settled (Benac 1985, 198), while more and more evidence for diffuse, open air settlement is coming to light in the East Adriatic zone (Čović 1983, 143-145; Mihovilić 2009; Sirovica 2015). Herding is a frequently encountered hypothesis for less conspicuous enclosed sites (Slapšak 1995, 26–27), which is corroborated by evidence for specialised (or intensive) pastoralism during the later prehistory, such as in the case of Rat hillfort on the Island of Brač and Pupićina cave in Istria (Miracle and Forenbaher 2006, 478; Gaastra et al. 2014). Some particular hillfort sites in Bosnia were interpreted as having a predominantly ritual function (Benac 1985, 20), while Gaffney et al. (2001, 152) argue that a good deal of Adriatic hillforts should be understood as “public monuments”, associated with control of land through performance of fertility rituals. It should be noted, however, that specifically ritual structures are generally lacking on hillforts (besides funerary constructions); without downplaying the importance of cult and ritual in these societies, it is difficult to substantiate claims for chiefly ritual purposes of hillfort enclosures.

In sum, Eastern Adriatic hillforts are still difficult to characterise, both chronologically and functionally. Nevertheless, there can be little doubt that these sites are a landscape phenomenon – conspicuous constructions set on high ground that often produce a sense of visual domination (for both observer on the site and passer-by in the local landscape). Due to their high density, one will usually have at least one hilltop site in visual range while moving across the terrain.

Considering seafaring and seaborne contact, there is ample archaeological evidence for regular exchange across the Adriatic from the Early Neolithic period onwards (Forenbaher 2009). The Eastern Adriatic Sea is relatively calm and dotted with a thousand or so closely spaced islands that provide ample shelter for seafaring activities. However, such an idyllic image needs to be balanced with potential sea raiding, particularly favoured by local geographical configurations and well documented from the Iron Age onwards (Bracewell 1992; Bandelli 2004; Mihovilić 2004).

Adriatic seafaring moved to a new scale during the Late Bronze Age period when the area became involved in a particularly important maritime connection linking the Eastern Mediterranean with Central Europe. A crucial site is the ‘international emporium’ of Frattesina, situated in the Po delta and flourishing in 12th and 11th c. BC (Bietti Sestieri et al. 2015). Exchange along the so-called amber route intensified, linking the Baltic with Greece, and first clearly Adriatic amber products appeared (Negroni-Catacchio 1999; Bellintani et al. 2015). The Northern Adriatic interaction zone developed simultaneously, indicated by wide circulation of portable objects and fast adoptions of new styles in local production (Blečić-Kavur 2014). A recent discovery of a sewn plank boat in Zambratija (NW Istria), dated to 1120 – 930 cal. BC by one sample, is also worth mentioning (Koncani Uhač and Uhač 2012). Some 5 to 6 meters of the boat’s length are preserved, which would be close to a half of its length (the research is still ongoing).

Recently, Borgna and Cassola Guida (2009, 99) emitted a hypothesis that Adriatic hillforts could have served as beacons for maritime navigation, which would link to similar claims for Bronze Age coastal sites on the Balearic Islands (Calvo et al. 2011). However, in both cases these are not specialised sites but rather settlements that enjoy a particular view of the sea or an exposed position on small islands and promontories. Apparently, there is a need to formulate models that account for both mundane settlement practices and a potentially privileged relationship with the sea.

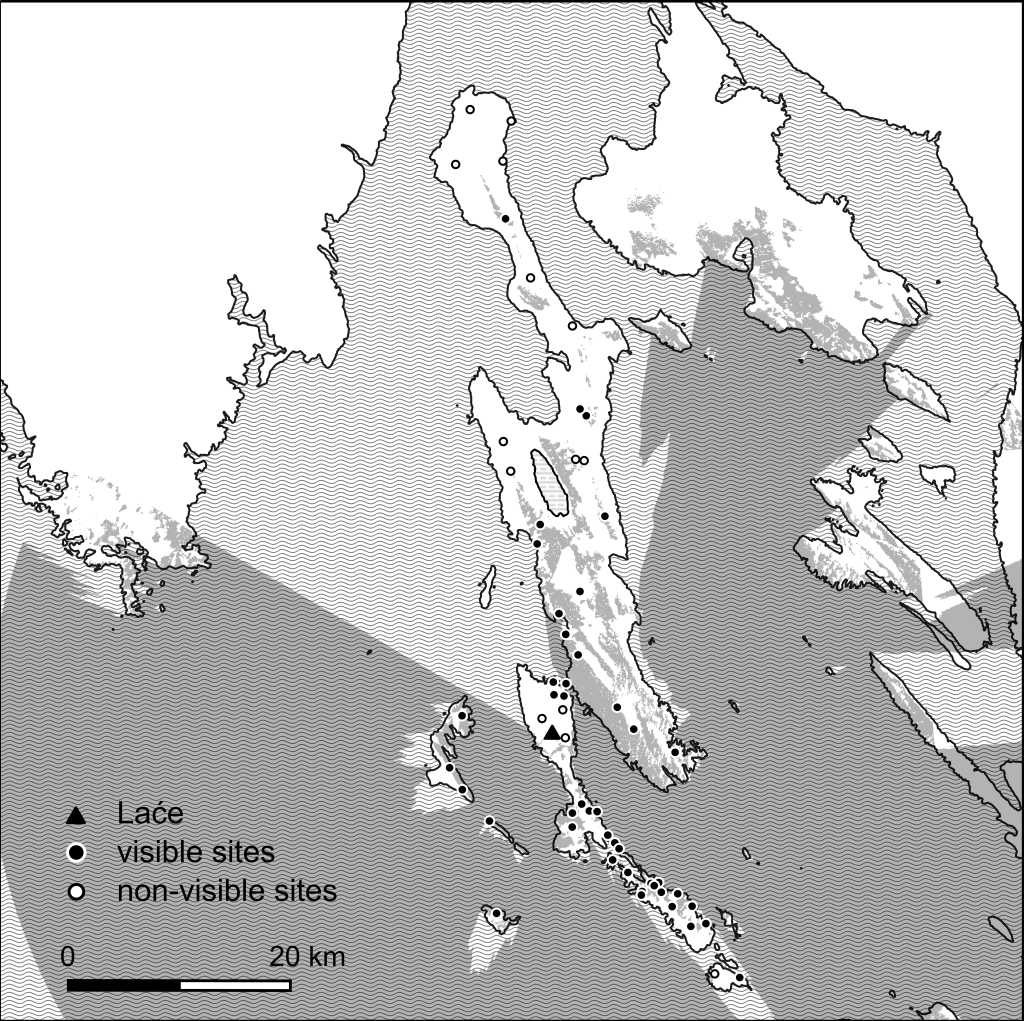

Figure 2. Prehistoric hillforts of Cres and Lošinj islands (see Appendix for full list).

The case of Cres and Lošinj islands

The islands of Cres and Lošinj are situated in the Kvarner Bay, Croatia (Figures 1 and 2). The islands are connected through an isthmus 100 m wide, thereby constituting the largest landmass in the Adriatic Sea (482 km2). Due to the narrowness of the isthmus and its probable severing already by the Roman period, if not earlier, the islands are usually considered as separate entities (Blečić-Kavur 2015). Both islands are rocky and rugged, culminating at 580 meters above sea level on Lošinj and some 600 meters on Cres. Viewed from the sea, both islands resemble a long, stony crest. As in much of the Adriatic, travel by sea would have been much more comfortable, if not faster, than by land, even when using simple seagoing vessels. The islands feature numerous natural harbours which influenced the development of important maritime stations, first in Osor, at the isthmus, prospering already by the Late Bronze Age and up till the medieval period (cf. supra), and then in Mali Lošinj, deep in the large bay in the middle the Lošinj island, which had its heyday in the 18th – 19th century, before the onset of steam-powered ships (Čoralić and Novosel 2014).

Prehistoric hilltop sites, which will be referred to as hillforts because of the usual presence of an enclosure, were first studied on Cres and Lošinj islands by Carlo Marchesetti (1924). During the 1950’s a tentative systematic research was undertaken by Vladimir Mirosavljević (1974). He made a series of trial trenches on most of hillfort sites he visited, accompanied with basic topographical sketches, but unfortunately passed away before publishing the material excavated. We can, therefore, consider there to be reasonably exhaustive topographic data, even if there is a number of inconsistencies across publications: sites that cannot be accurately located or seem problematic in published descriptions are designated as hypothetical (Figure 2).

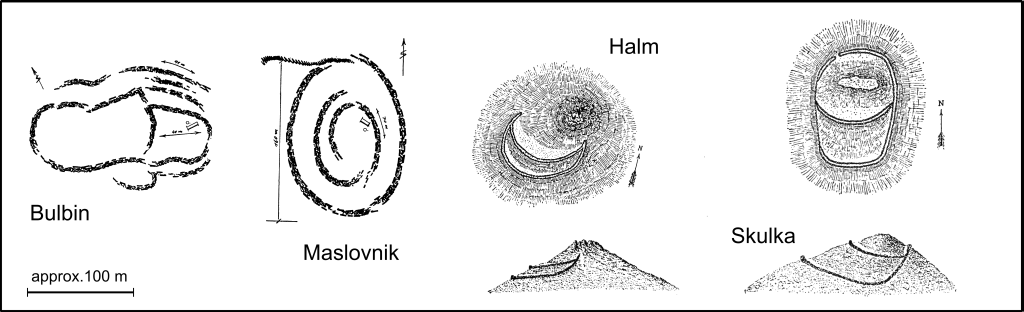

Figure 3. Some examples of hillfort layouts (left to right: Mirosavljević 1974, fig. 10 and 8; Marchesetti 1924, fig. 2 and 13).

The majority of hillfort sites cannot be dated due to the lack of published reports on discovered archaeological finds. What has been published, however, often seems too selective (sometimes 5 or 6 pieces of pottery per site) and/or generally lacks a thorough discussion on the possible chronological range represented. In any case, the majority of finds can be safely placed into the Middle to Late Bronze Age (approx. 1600 to 900 BC; Marchesetti 1924, 140; Cardarelli 1983; Ćus-Rukonić and Glogović 1989, 496).

In the 12th c. BC rich grave goods appear at the necropolis of Osor (mostly personal ornaments such as pins, fibulae and bracelets) although there are also some earlier finds from the site (Ćus-Rukonić and Glogović 1989, 495-496). From that period onwards, the site situated at 150 to 200 meters wide isthmus connecting Cres and Lošinj (its width depending on ancient sea level: Antonioli et al. 2007), took a leading role in the local settlement system. Grave finds dating from the Iron Age, such as amber artefacts, military equipment and bronze buckets (situlae), testify to development of a local commercial and political centre (Blečić-Kavur 2015). There is no clear archaeological information on a potential canal cutting through the isthmus, but this obstacle would still have been easily negotiated by hauling boats.

The Iron Age, the beginning of which is variously dated between 12th and 9th c. BC in the North-Adriatic region (Bietti Sestieri 2009; Mihovilić 2013, 115ff; Blečić-Kavur 2014), is rather problematic on Cres-Lošinj hillforts. Apart from the wealth of material from the Osor necropolis, attached to a major but unexplored settlement, Iron Age finds are relatively unheard of from other settlements (eg. site No. 7: Marchesetti 1924, 128; Mirosavljević 1960, 215; probably site No. 3: Blečić-Kavur 2014, 27).

In sum, rather than providing dates for individual sites, according to the present state of research it is only possible to postulate a peak of hillfort use on Cres-Lošinj archipelago in the wide range of Middle to Late Bronze Age, possibly extending into the Iron Age. There seems to be a decline in the number of occupied hillforts in the Iron Age, if we are to judge by the published material, which would reflect the similar tendency in neighbouring Istria (cf. supra). Strict contemporaneity of the sites cannot be attested, but we can still pose the question on the basis of their spatial density. Moreover, if hillforts are considered as a landscape element, their agency must have continued for some time beyond the date of abandonment.

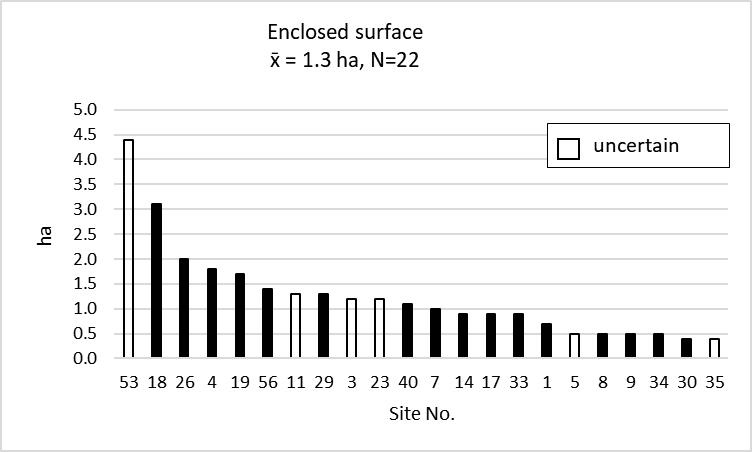

Figure 4. Approximate sizes of enclosed areas.

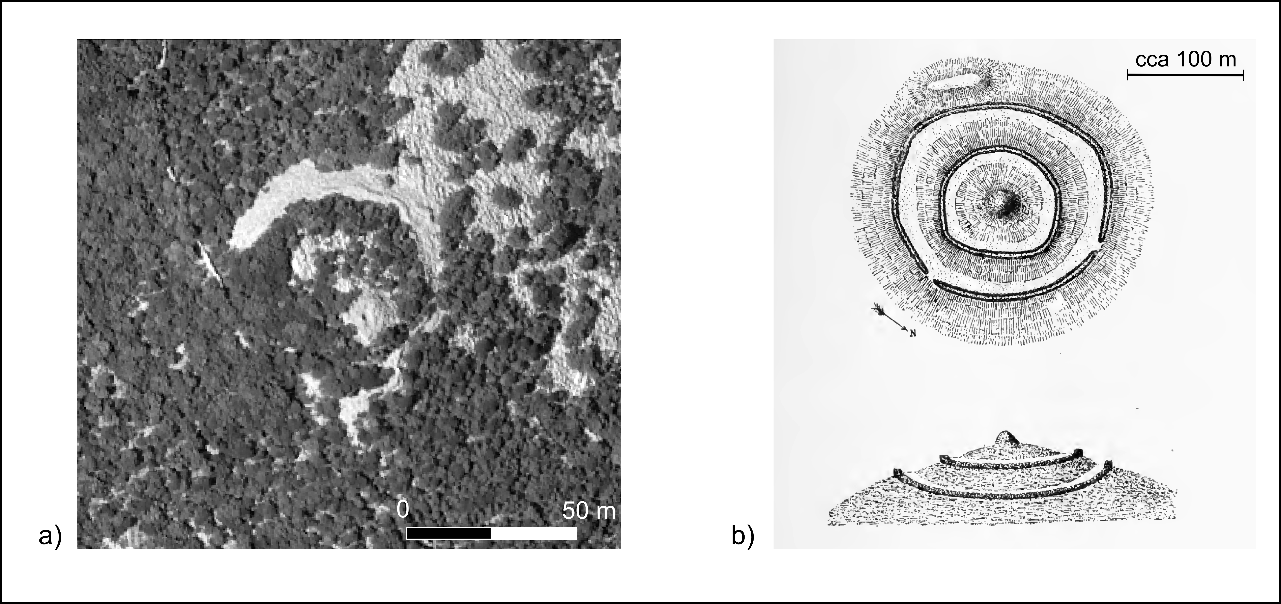

A particular problem is the original function of hillfort sites, as little evidence exists to determine what this may have been. A general overview of sizes of the enclosed areas can be obtained through published plans and aerial imagery: apparently, the sites are quite small, normally below two hectares (Figure 4). Mirosavljević (1974, 270) mentions traces of postholes and domestic architecture on several sites, albeit without much detail. In any case, most of the hillforts could not have been important settlements, not only because of their size but also due to the ruggedness of neighbouring terrain. In particular, sites occupying very high prominences, such as Sis on the second highest peak of Cres (No. 5) and Laće just below the highest peak of Lošinj (No. 30), cannot be listed as candidates for permanent settlement; there is only bare stone and wind to be found there. Some of the sites feature a large mound on the highest point within the enclosure, which is characteristic for Kvarner bay and Istria (Figure 5). The chronological and functional relationship between these constructions and enclosures is not known due to a lack of research. In some particular cases such as the site of Bog/Vela Straža (No. 21) it seems that the enclosure is subsidiary to the mound, i.e. the enclosed space is small and rugged, leaving very limited surface for potential habitation or other activities (Figure 5). Therefore, the possibility of primarily symbolically charged monument should not be excluded.

Figure 5. Bog/Vela Straža on Lošinj island (No. 21; DGU 2015) and Gradina near Malinska, Island of Krk (Marchesetti 1924, 124; Fig. 1).

These remarks lead us to the issue of how the term hillfort site can be defined. Apparently, it could be anything from a permanently settled stronghold to a pastoral enclosure or a symbolically charged monument. However, it remains that these sites somehow look alike, they occupy high topographies and originally they featured more or less massive drystone walls (which are today visible as wide, low rubble embankments). Moreover, quantities of domestic pottery reported on most sites indicate a certain intensity of human involvement. We cannot simply dismiss hillforts as too vague, useless a category; I shall expand on this problem below by regarding these sites not only as a trace, but also as a (visible) statement on human settlement.

Explaining the pattern

Some 40 to 50 hillfort sites were recorded on Cres and Lošinj (considering the level of uncertainty in the published reports), but curiously, more than half of them are packed onto the island five times smaller. With close to 30 sites on 74 km2 the island stands out by such anomalous density, in contrast to the rather typical hillfort landscape of Cres. Some islands do come close, however, such as tiny Molat with 4 hillforts on 22 km2 (Batović 1977, 210). Indeed, even the smallest theoretically inhabitable islands were chosen for hillfort construction: Unije has two, possibly three such sites on 16.8 km2, while Srakane, covering a mere 1.2 km2 is also crowned by a hillfort (Figure 2). The problem of such unexpected densities and seemingly inappropriate site locations will be examined here in the case of Lošinj.

A first hypothesis might relate the density of sites to a higher population density and possible protection of local territories. However, as discussed above, the intensity of settlement inside hillforts is highly problematic and cannot be assessed through available data. What is more, the Lošinj Island is an elongated stony crest and does not provide large tracts of easily cultivated terrain. Medieval historical sources are explicit on very low population density on the island (Čoralić and Novosel 2014). The rise in the economic importance of the island in the Modern period is primarily related to fishing and then shipping from the 17th century onwards (ibid). Even if we cannot project the situation in historical periods to prehistory, it seems quite clear that the island has low carrying capacity in terms of agricultural production and, conversely, that it offers good potential for development of maritime affairs. Therefore, considering minuscule territories around Bronze Age hillforts, 2 or 3 square kilometres, does not seem an appropriate model.

Figure 6. Viewshed from Laće hilltop site (radius of analysis: 50 km).

Frequently, hillforts are interpreted as parts of defence systems, enabling surveillance and control (implicitly aggressive) of the surrounding territory, which in the case of Lošinj island should obviously be considered as the control of maritime travel. Regarding surveillance, the island is endowed with an ideal observation outpost on the Osoršćica hill, almost 600 meters high, which, as a matter of fact, hosts the enclosed site of Laće on its crest (No. 30). This site not only commands an unobstructed view of the wider seascape, but also maintains a direct visual link with a larger part of the island which is very useful for quick signalling (Figure 6). However, if that site would have sufficed, what are we to make of the rest? Perhaps closer visual contact with potential seafarers would have been preferred in prehistory, necessitating a higher number of outposts, but in that case a maximum of a dozen outposts would be largely sufficient, regarding less than 30 km of island’s length and the availability of suitable positions on its stony crest. Some 30 hillforts is far too much for simple visual control.

Considering the hypothetical organisation and active control of sea routes, there is at least one site that probably entertained such a role: Osor at the Cres-Lošinj isthmus. There is no doubt that the settlement owed its prosperity to maritime travel, across or through the isthmus, especially from the 12th century BC onwards (cf. supra). However, harbours are (partly) specialised sites, featuring facilities necessary for maritime affairs as well as possible fleet for trading, raiding or patrolling purposes – no more than a couple of such sites would be sufficient for a small island. Significantly, Osor is unrivalled on both islands in terms of archaeological heritage. If Lošinj hillforts were indeed related to seafaring, at least those in proximity of the shore, one can only envisage a model of local and close -range seafaring, which is not dependant on specialised harbour facilities (cf. Tartaron 2013, 192).

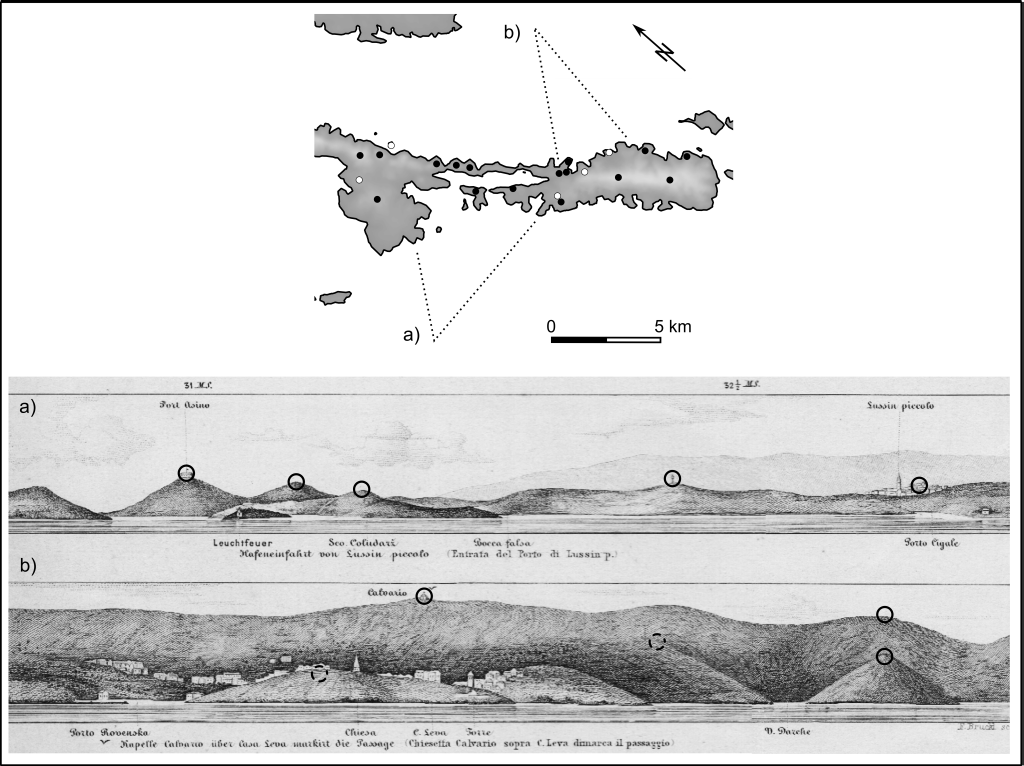

Figure 7. Panoramas of Mali Lošinj (above) and Veli Lošinj (below) harbours, viewed from the sea (k.u.k. Kriegsmarine 1872). Prehistoric hillforts are marked with circles (dashed line for uncertain sites).

The hypotheses exposed so far belong to the classical repertoire of archaeological discourse on hillforts which is typically focused on the subordination of the surrounding social landscape to these singular sites. Let us now reverse this perspective and analyse the one of a passer-by, seafarer in particular. This will also require stepping out from the usual bird’s eye view of a topographic map and consider a series of vistas evolving in front of the traveller. A century ago such vistas accompanied nautical charts, such as the one on Figure 7. Rather than scenic decorations, these sketched panoramas were a valuable aid when navigating close to the coast. The visual impact of hillfort sites, or at least their visual exposition, becomes apparent once they are plotted onto the 19th c. vista: they crown the horizon on the back of Lošinj ridge. Note that hillforts sometimes occupy places that are particularly noticeable on the map, such as the hilltop chapel on Mt. Calvario (No. 54), the fortress of Asino (No. 42) or places adjacent to church towers. Prehistoric hillforts would, then, make ideal landmarks: they were built upon prominent points on the horizon and their drystone ramparts could have been easily recognisable if cleared from vegetation.

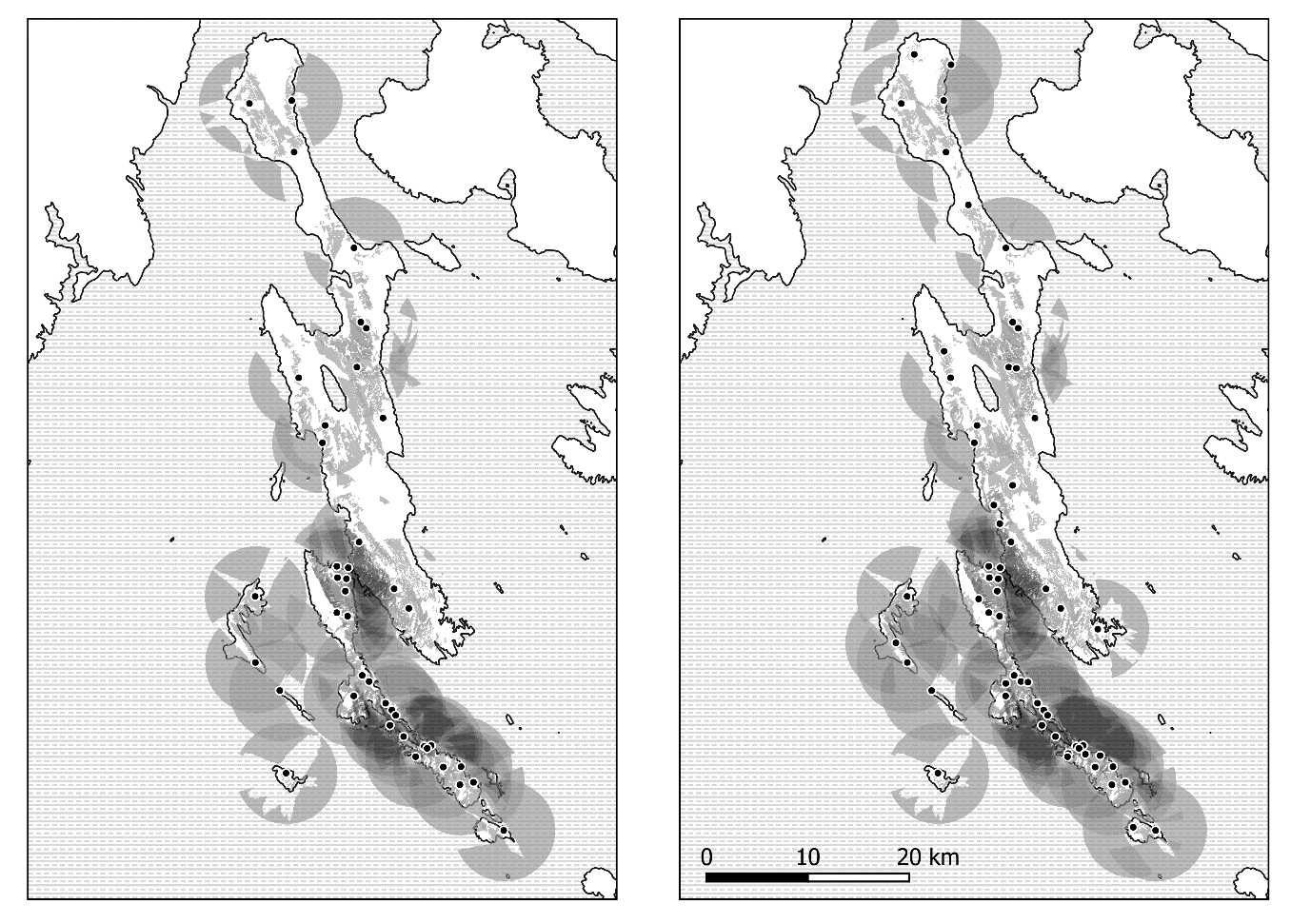

The intensity of such visual presence can be verified using viewshed analysis which determines potentially visible areas from a given location (Llobera 2003; Conolly and Lake 2006, 228-233). This type of analysis is made over a digital terrain model, in our case an elevation grid of 25 meters resolution, made by photogrammetric restitution (DGU 2011). The Viewshed analysis Quantum GIS plugin was used to perform the calculation (Čučković 2016). The analysis radius was set to 5 km, which is in the lower part of the range from which vistas on Figure 7 were made (between 5 and 8 km). Such a restricted range is used because we are not interested in what hillfort inhabitants could see, but rather from which areas their settlements could be clearly seen. Theoretically, large objects such as hillfort ramparts could be seen from much farther away; for example, provided with the best atmospheric conditions and perfect visual acuity of 1 minute of angle, an object measuring 5 meters (on its smaller side) can be perceived from a distance of 17 km (Ogburn 2006). However, visual perception of objects in the landscape is a complex problem, not least because such ideal conditions are rarely met (air clarity, contrast against the background, etc.: Shang and Bishop 2000). The 19th century vistas are probably a safer guide to optimal distances at which the coast-scape would provide useful detail.

Figure 8. Viewshed analysis for attested prehistoric sites (left) and all recorded sites (right). Maximum visibility distance is set to 5 km.

The highest frequencies of visual presence of hillforts can be found around good harbour sites, namely the Lošinj Bay and Osor (Figure 8). It seems that the route following the inner (eastern) coast of Lošinj and leading to the isthmus was particularly scenic in terms of visible hillforts. Sites on smaller islands complement this coverage on the westward side. In contrast, hillforts of the island of Cres are somewhat further in the interior and not as exposed to the sea. Furthermore, the island is relatively sparsely populated with hillforts, in spite of its much larger size.

Now, Lošinj is but one narrow limestone crest where the majority of elevated positions open onto a sea view. However, this only makes it more curious that it attracted so many hillfort constructions in comparison to neighbouring Cres, because Lošinj’s stony, karstic environment does not offer any particular advantage in terms of agricultural or pastoral production. What sets these two islands apart is, rather, their maritime setting inside Kvarner Bay. Lošinj is a historical stopover along the coastal sea route, while remote and sparsely inhabited Cres clung to a pastoral economy until recent times. Even if hillforts would seem essentially to be a terrestrial affair, we need to include this geographical parameter in our explanatory models, namely the response to the local seascape.

To recapitulate, the anomalous density of hillforts on Lošinj Island cannot be explained by common models (territorial control, surveillance or organisation of maritime networks). That is not to say that hillforts were not used for such purposes, but rather that at least one more factor should be taken into account, namely some kind of ostensible display. I would propose that Lošinj hillforts, and by extension similar sites on otherwise inhospitable locations in the Adriatic, were put into the service of a particular cultural strategy of emphasising human occupation not only of the land but also of the sea.

Conclusion: demonstrative settlement on the Adriatic seaboard

At first, Cres and Lošinj hillforts can be understood through costly signalling paradigm: the apparent amount of work invested displays the vitality of the settled community. Hillfort locations are highly visible in the surrounding landscape which only adds to their signalling capacity; they thus become statements in the cultural landscape.

However, we are dealing here with a particular settlement pattern and a way of life, while costly signals are typically considered as occasional and more or less opposed to subsistence practices. The hillforts in question normally show traces of more or less intensive human activities and even in the absence of reliable data, and regardless of possible ritual functions, should be understood as related to domestic or subsistence activities (cf. Bradley 2005 for a critique of the ritual vs. domestic dichotomy). The problem, thus, is not to distinguish between wasteful and economical practices, but rather to understand the integration of costliness as a cultural value across the social system (i.e. the ontology of cost). In other words, at what cost does a culture come, how are these costs defined, and how are they distributed across constituent groups and individuals?

Another problem is the historical and discursive character of human communication. Signals, along with their intended meaning and their subsequent perception, evolve over time and specifically in relation to preceding signals/statements. One may speculate that accumulation of monuments in a landscape would lead to saturation and debasement of their message, unless practices of their removal, either physically or on the level of discourse, be devised (Glatz and Plourde 2011, 39). We need to acknowledge that culturally embedded signalling practices may, and often do, develop within and in relation to fields of discourse where neither the emitter nor the receiver need occupy a central role. It is in particular the discourse backed by a strong material support that may take a life of its own (think of scholarly publishing or graffiti). Therefore, we need to consider hillforts in their own terms, as participating to a long -established discourse in the landscape, but without reverting to the notion of “local tradition” that exists outside the discourse.

Issues of cultural embeddedness, discursivity and historical contingency of costly signals may seem opaque, but their understanding is crucial if the specific problem of the hillfort landscape is to be addressed. For one thing is certain, the entire landscape cannot be a signal in the same manner as a singular event or a simple structure built over a short time span. There could not have been a grand design for constructing a particular number of hillforts in particular locations during the Bronze Age on the Cres and Lošinj islands: landscapes are composites of heterogeneous signals, human and natural, past and present. Yet, as in our case study, coherence can sometimes be observed, human actions may bring diverse signals into a comprehensive message. Visibility analysis indicates that the site distribution can be understood as a meaningful whole: it is when viewed from the sea, en masse, that hillforts start to make sense. This implies that hillfort landscape arose neither as a historical coincidence, nor as a passive accumulation. I propose to consider the examined hillfort landscape as reflecting demonstrative settlement, a historical process and a meaningful discourse. The concept is, perhaps, best explained by what it is not.

Settlement is not understood as a thing or a collection of things but rather as a process. To a Croatian speaker, used to a particular verbal system, the English term ‘settlement’ may raise a curious ambiguity: at what point does the word cease to indicate a process of settling down to denote a settled place, a thing? Concerning our problem: at what point, and in what circumstances, does settlement of a place or a region become an accomplished act (if ever)? Archaeological studies often consider individual settlements as part of historical processes, but that is more often than not a question of chronology and sequences of occupation levels. However, each act of ‘settling down’, which sensu lato may be any human action in the landscape, is yet another engagement with both the material world (cultural and natural) and the social matrix through which it was initiated. In other words, each settling act is responding to and working upon a particular discourse, sometimes seeking conformity and sometimes demarcation. The elements of conformity, in particular to a general ‘worldview’ or cosmology, tend to be stressed by archaeologists when considering the symbolic aspect of settlement practices (cf. David 2002, 3ff.), but that is only one segment of a larger web of associations and references. Such a broad framework may include anything from subsistence practices, which support the settlement system, to social competition and political rivalries. Development of Adriatic hillfort landscapes can, thus, be understood as a process of settlement, a perpetually unfinished state of affairs that needed repeated adjustments and insertions of new statements, architectural or other.

Demonstrative quality is not understood as one-way signalling, from signaller to potential responder, but rather as participation to a common field of discourse which is both, historical and to a certain extent independent of its participants. There is certainly much overlap between notions of field of discourse and those of culture, ideology or worldview. However, the idea of discourse, in particular as advocated by Foucault, attempts to overcome the problem of meaning that exists behind the scenes, in peoples’ minds or in some mysterious cultural code, while organising and driving the exchange of statements (Foucault 1969, 36; 182). He is specifically concerned with the construction of meaning through discursive practice, by re-combinations of statements within larger fields of discourse. From this perspective, the ‘ostensible display’ can no longer be understood simply as a particular function of hillforts, a series of outbound signals conveying some culturally encoded meaning; it is rather a constitutive feature of a wider field of discourse. Such discourse could have been reflected in mortuary monuments, in particular cairns and barrows that dot the Adriatic landscape, but which are very poorly researched on Cres and Lošinj Islands (Ćus-Rukonić and Glogović 1989, 495). Likewise, the pastoralist landscape that most probably surrounded prehistoric Adriatic hillforts, and to which they belonged, materialised a variety of symbolically charged practices linking past communities to the land (cf. Hoaen and Loney 2013).

The islands of Cres and Lošinj were chosen for the analysis because of their particular environmental setting, as “island laboratory” (Bevan and Conolly 2013, 6), but it has to be stressed that the hillfort landscape of the islands does not seem to be essentially different from their terrestrial counterparts, namely in neighbouring Istria. As already stressed, the Adriatic Sea should be understood as a medium of connection rather than of division. A host of questions thus arise: what is the difference, if any, between the seaward and earthbound display? What is the relationship between the composition of potential public (sea bound or terrestrial, local or foreign) and the development of the landscape wide discourse? The notion of discourse can help to address these questions from a more productive angle than the notion of simple signalling. The latter cannot resolve the dilemma between a strictly utilitarian, evolutionary idea of individualistic, competitive behaviour that is an explicitly local affair – i.e. of a restricted population within its confined environmental niche – and the more conventional idea of a wider cultural tradition of hillforts, existing on a larger geographical scale, but which necessarily becomes a sort of a blueprint that mysteriously guides and orders social practice. It may be more fruitful, for example, to consider a transplanted or borrowed discourse, with all its intricate references and practices, and its possible adaptation to a new social and geographical environment.

The idea of demonstrative settlement is inspired by costly signalling theory, but specifically targets its two major problems: the separation of symbolic aspects from those which are functional, and the tendency to reduce culturally-embedded signs to isolated signals. From that standpoint neither particular pieces of architecture nor individual events can be considered costly because of some inherent characteristic (namely, the amount of energy invested); it is rather their insertion in a wider cultural system, as well as in a particular exchanges of material statements, a discourse, that enables them to function as costly signals. The analysis of Adriatic hillforts revealed that they become more understandable in the context of assertive display towards potential seafarers. However, this is not to add one more function to already charged repertoire (pastoralism, habitation, political control, materialisation of ideology etc.). Once again, demonstrative settlement is participation to a discourse which is necessarily symbolic and material; more specifically it deals with the mode of such participation. If function is what things do, or what we do with them, then such mode should better be understood as relative position within the larger cultural context, a set of references to other statements. Adriatic hillforts and specifically those of the island of Lošinj could then be understood as a series of overstatements of presumably sparse settlement of small islands, overstatements repeated over a considerable period of time, resulting in a network of conspicuous strongholds.

Acknowledgments

I was able to briefly examine the material from old Mirosavljević’s excavations which is held in the depot of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts thanks to kindness of archaeologist Branka Migotti. Comments and a valuable help with bibliography were also provided by Martina Blečić-Kavur and Stašo Forenbaher. All possible lacunae are entirely mine.

Bibliography

Antonioli, F., M. Anzidei, K. Lambeck, R. Auriemma, D. Gaddi, S. Furlani, P. Orrù, E. Solinas, A. Gaspari, S. Karinja, V. Kovačić, L. Surace. 2007. “Sea-level change during the Holocene in Sardinia and in the northeastern Adriatic (central Mediterranean Sea) from archaeological and geomorphological data.” Quaternary Science Reviews 26: 2463–2486. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.06.022

Bandelli, G. 2004: “La pirateria adriatica di età repubblicana comme fenomeno endemico.” In La pirateria nell’Adriatico antico, edited by L. Braccesi, Hesperìa 19, 61–68. Rome : L’Erma di Bertschneider.

Barbaro, B., A. Cardarelli, I. Damiani, F. di Gennaro, N. Ialongo, A. Schiappelli, F. Trucco. 2013. “Monte Cimino (Soriano nel Cimino, VT): un centro fortificato e un complesso cultuale dell’età del Bronzo Finale.” Scienze dell’Antichità 19 (2-3): 15–18.

Batović, Š. 1977. “Caractéristiques des agglomérations fortifiées dans la région des libourniens.” Godišnjak Centra za balkanološka ispitivanja 15: 201–225.

Bellintani, P., L. Salzani, G. de Zuccato, M. Leis, C. Vaccaro, I. Angelini, C. Soffritti, M. Bertolini, U. Thun Hohenstein. 2015. “L’ambra dell’insediamento della tarda Età del bronzo di Campestrin di Grignano Polesine (Rovigo).” In Preistoria e Protostoria del Veneto, edited by G. Leonardi and V. Tiné, Studi di Preistoria e Protostoria 2, 419–426. Florence: Instituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, Soprintendenza Archeologia del Veneto, Università degli Studi di Padova.

Bell, T. and G. Lock. 2000: “Topographic and cultural influences on walking the Ridgeway in later prehistoric times.” In Beyond the map: Archaeology and Spatial Technologies, edited by G. Lock, 85–100. Amsterdam, Berlin etc.: IOS Press.

Benac, A. 1985. Utvrđena ilirska naselja I: Delmatske gradine na Duvanjskom polju, Buškom blatu, Livanjskom i Glamočkom polju, Djela ANUBiH 60. Sarajevo: Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine.

Bevan, A. and J. Conolly. 2013. Mediterranean Islands, Fragile Communities and Persistent Landscapes: Antikythera in Long-Term Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bietti Sestieri, A. M. 2009. “L’età del Bronzo Finale nella penisola italiana.” Padusa, Bollettino del Centro Polesano di Studi Storici, Archeologici ed Etnografici, new series, 44/2008, 7–54.

Bietti Sestieri, A. M., P. Bellintani, L. Salzani, I. Angelini, B. Chiaffoni, J. De Grossi Mazzorin, C. Giardino, M. Saracino, F. Soriano. 2015. “Frattesina: un centro internazionale di produzione e di scambio nell’Età del bronzo del Veneto.” In Preistoria e Protostoria del Veneto, edited by G. Leonardi and V. Tiné, Studi di Preistoria e Protostoria 2, 427-436. Florence: Instituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, Soprintendenza Archeologia del Veneto, Università degli Studi di Padova.

Blečić-Kavur, M. 2014. Na razmeđu svjetova za prijelaza milenija: kasno brončano doba na Kvarneru / At the crossroads of worlds at the turn of the millennium: the Late Bronze Age in the Kvarner region, Musei Archaeologici Zagrabiensis Catalogi et Monographiae vol. XI. Zagreb: Archaeological Museum in Zagreb.

Blečić-Kavur, M. 2015. Povezanost perspective: Osor u kulturnim kontaktima mlađeg željeznog doba / A coherence of perspective: Osor in cultural contacts during the Late Iron Age. Koper: University of Primorska, Mali Lošinj: Museum of Lošinj.

Bliege Bird, R. and E. A. Smith. 2005. “Signaling Theory, Strategic Interaction, and Symbolic Capital.” Current Anthropology 46(2): 221–248. doi: 10.1086/427115

Borgna E. and P. Càssola Guida. 2009. “Seafarers and Land-Travellers in the Bronze Age of the Northern Adriatic.” In A Connecting Sea: Maritime Interaction in Adriatic Prehistory, edited by S. Forenbaher, BAR International Series 2037, 89–104. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Bourdieu, P. 1994. Raisons pratiques : sur la théorie de l’action. Paris: Seuil.

Bourdieu, P. 1979. La Distinction. Critique sociale du jugement. Paris: Editions de Minuit.

Bracewell, C.W. 1992. The Uskoks of Senj: Piracy, Banditry, and Holy War in the Sixteenth-Century Adriatic. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Bradley, R. 1982. “The Destruction of Wealth in Later Prehistory.” Man, New Series, 17 (1): 108–122.

Bradley, R. 2005. Ritual and Domestic Life in Prehistoric Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

Buršić-Matijašić, K. 2007. Gradine istre: povijest prije povijesti. Pula: Zavičajna naklada “Žakan Juri”.

Caillé, A. 2005. Don, intérêt et désintéressement. Bourdieu, Mauss, Platon et quelques autres. Paris: La Découverte.

Cardarelli, A. 1983. “Castellieri nel Carso e nell’Istria: cronologia degli insediamenti fra media età del bronzo e prima età del ferro.” In Preistoria del Caput Adriae, edited by A. Boiardi and G. Bartolomei, 87–112. Trieste: Istituto per l’Enciclopedia del Friuli Venezia Giulia, Udine.

Calvo, M., D. Javaloyas, D. Albero, J. Garcia-Rosselló and Víctor Guerrero. 2011. “The ways people move: mobility and seascapes in the Balearic Islands during the late Bronze Age (c. 1400–850/800 BC).” World Archaeology 43(3): 345–363. doi:10.1080/00438243.2011.605840

Chapman, J., R. S. Shiel and Š. Batović. 1987. “Settlement Patterns and Land Use in Neothermal Dalmatia, Yugoslavia: 1983-1984 Seasons.” Journal of Field Archaeology 14 (2), 123–146.

Conolly, J. and M. Lake. 2006: Geographical Information Systems in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Čoralić, L. and F. Novosel. 2014. “Lošinjanin Petar Vicko Petrina (1750. – 1829.), zapovjednik mletačkih ratnih brodova koncem 18. stoljeća.” Povijesni prilozi 46: 257–286.

Čović B. 1983. “Regionalne grupe ranog bronzanog doba.” In Praistorija jugoslavenskih zemalja IV, Bronzano doba, edited by A. Benac, 114–190. Sarajevo: Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine.

Čović, B. 1989. “Posuška kultura.” Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Sarajevu, new series, 44: 61–127.

Čučković, Z. 2016. “Advanced viewshed analysis: a Quantum GIS plug-in for the analysis of visual landscapes.” The Journal of Open Source Software 4 (1). doi:10.21105/joss.00032

Ćus-Rukonić, J. and D. Glogović. 1989: “Pregled nalaza i nalazišta na otocima Cresu i Lošinju.” Arheološki vestnik 39-40/1988-1989: 495–508.

David, B. 2002. Landscapes, Rock-Art and the Dreaming: An Archaeology of Preunderstanding. London: Bloomsbury.

DeMarrais, E., J. L. Castillo and T. Earle 1996. “Ideology, Materialization, and Power Strategies.” Current Anthropology 37 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1086/204472

De Souza, J. G., R. Corteletti, M. Robinson, J. Iriarte. 2016. “The genesis of monuments: Resisting outsiders in the contested landscapes of southern Brazil.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41: 196–212. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2016.01.003.

DGU. 2011. Digitalni model reljefa (DMR 25). Zagreb: Državna geodetska uprava. [DEM at 25 meter resolution].

DGU. 2015. Digitalna ortofoto karta u boji (DOF). Zagreb: Državna geodetska uprava, [Digital colour orthophotos, image acquisition in 2011, last accessed on September 30, 2015.]

Foucault, M. 1969. L’archéologie du savoir. Paris: Gallimard.

Forenbaher, S. (ed.). 2009. A Connecting Sea: Maritime Interaction in Adriatic Prehistory, BAR International Series 2037. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Gaastra, J.S., E. Cristiani and V. Barbarić. 2014. “Herding and Hillforts in the Bronze and Iron Age Eastern Adriatic: Results of the 2007- 2010 Excavations at Gradina Rat / Stočarstvo i gradine na istočnom Jadranu u brončano i željezno doba: rezultati iskopavanja na gradini Rat 2007.-2010.” Vjesnik za arheologiju i historiju dalmatinsku 107: 9–30.

Gaffeny, V., S. Čače, B. Kirigin, P. Leach and Nikša Vujnović. 2001. “Enclosure and Defence: the Context of Mycenean Contact within Central Dalmatia.” In Defensive Settlements of the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean after C. 1200 B.C.: Proceedings of an International Workshop Held at Trinity College Dublin, 7th-9th May, 1999, edited by V. Karageorghis and C. Morris, 137–156. Nicosia: Trinity College Dublin and Anastasios G. Leventis Foundation.

Glatz, C. and A. M. Plourde. 2011. “Landscape Monuments and Political Competition in Late Bronze Age Anatolia: An Investigation of Costly Signaling Theory.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 361: 33–66. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.361.0033

Govedarica, B. 1982. Prilozi kulturnoj stratigrafiji praistorijskih gradinskih naselja u jugozapadnoj Bosni, Godišnjak Centra za balkanološka ispitivanja 20: 111–188.

Govedarica, B. 1989. Rano bronzano doba na području istočnog Jadrana, Djela ANUBiH 67. Sarajevo: Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine.

Hamilton, S. and J. Manley. 2001. “Hillforts, Monumentality and Place: A Chronological and Topographic Review of First Millennium BC Hillforts of South-East England.” European Journal of Archaeology 4 (1): 7–42. doi: 10.1177/146195710100400101

Hänsel, B., D. Matoševic, K. Mihovilić and B. Teržan. 2009. “Zur Sozialarchäologie der befestigten Siedlung von Monkodonja (Istrien) und ihrer Gräber am Tor.” Praehistorische Zeitschrift 84 (2): 151–180. doi:10.1515/PZ.2009.008

Hänsel, B., K. Mihovilić, B. Teržan. 2016. Monkodonja. Istraživanje protourbanog naselja brončanog doba Istre. Knjiga 1. Iskopavanje i nalazi građevina. / Monkodonja. Forschungen zu einer protourbanen Siedlung der Bronzezeit Istriens. Teil 1: Die Grabung und der Baubefund, Monographs and catalogues, Archaeological Museum of Istria, 25. Pula: Archaeological museum of Istria.

Hoaen, A. W. and H. L. Loney. 2013. “Landesque Capital and the development of the British uplands in later prehistory: investigating the accretion of cairns, cairnfields, memories and myths in ancient agricultural landscapes.” In Memory, Myth and Long-Term Landscape Inhabitation, edited by A. M. Chadwick and C. D. Gibson, 124–145. Oxford: Oxbow.

Hodgson, D. 2017. “Costly signalling, the arts, archaeology and human behaviour.” World Archaeology [current volume, pages not attributed] doi:10.1080/00438243.2017.1281757

Johnson, M. H. 2011. “A Visit to Down House: Some Interpretive Comments on Evolutionary Archaeology.” In Evolutionary and Interpretive Archaeologies: a Dialogue, edited by E. E. Cochrane and A. Gardner, 307–324. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press.

Knapp, A. B., and W. Ashmore. 1999. “Archaeological Landscapes: Constructed, Conceptualized, Ideational.” In Archaeologies of Landscape: Contemporary Perspectives, edited by W. Ashmore and A. B. Knapp, 1-30. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell.

Koncani Uhač, I. and M. Uhač. 2012. “Prapovijesni brod iz uvale Zambratija – prva kampanja istraživanja.” Histria Antiqua 21: 533–538.

k.u.k. Kriegsmarine. 1872. Lussin und Selve. Trieste: Hydrographisches Amt der k.u.k. Kriegsmarine. [Navigational map, 1868 survey, cartography by T. Oesterreicher.]

Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Llobera, M. 2003. “Extending GIS-based visual analysis: the concept of visualscapes.” International Journal of Geographical Information Science 17 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1201/9781420006377.ch20

Llobera, M. 2012. “Life on a pixel: challenges in the development of digital methods within an ‘interpretive’ landscape archaeology framework.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 19 (4): 495–509. doi:10.1007/s10816-012-9139-2

Marchesetti, C. 1903. “I castellieri preistorici di Trieste e della regione Giulia.” Atti del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Trieste X, new series vol. IV: 1–206.

Marchesetti, C. 1924: “Isole del Quarnero: ricerche paletnologiche.” Notizie degli scavi di antichità, 21 (5): 121–148.

Mauss, M. 2007. Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques. Paris : Presses universitaires de France [Originally published in Année Sociologique, seconde série, 1923-1924]

McGuire, K. R. and W. R. Hildebrandt. 2005. “Re-Thinking Great Basin Foragers: Prestige Hunting and Costly Signaling during the Middle Archaic Period.” American Antiquity 70 (4): 695–712. doi:10.2307/40035870

Mihovilić, K. 2004. “La situla di Nesazio con naumachia.” In La pirateria nell’Adriatico antico, edited by L. Braccesi, Hesperìa 19, 93–107. Rome: L’Erma di Bertschneider.

Mihovilić, K. 2009: “Gropi – Stari Guran. Analiza prapovijesne keramike.” Histria archaeologica 38-39/2007-2008: 37–79.

Mihovilić, K. 2013: Histri u Istri: željezno doba Istre / Gli Istri in Istria: L’età del ferro in Istria / The Histri in Istria: The Iron age in Istria, Monographs and catalogues, Archaeological Museum of Istria, 23. Pula: Archaeological museum of Istria.

Mihovilić, K., B. Hänsel, D. Matošević and B. Teržan. 2011. “Burial mounds of the Bronze Age at Mušego near Monkodonja, results of the excavations 2006-2007.” In Ancestral Landscapes: Burial mounds in the copper and Bronze ages (Central and Eastern Europe – Balkans – Adriatic – Aegean, 4th-2nd millennium B.C.), edited by E. Borgna and S. Müller-Celka, Travaux de la Maison de l’Orient 58, 367–373. Lyon: Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée.

Miletić, I. 2002. “Arheološka topografija otoka Unije.” Histria archaeologica 33: 195–263.

Miracle, P. and S. Forenbaher. 2006. “Changing Activities and Environments at Pupićina Cave / Promjene aktivnosti i krajolika oko Pupićine peći.” In Prehistoric Herders of Northern Istria. The Archaeology of Pupićina Cave – Pretpovijesni stočari sjeverne Istre. Arheologija Pupićine peći, edited by P. Miracle and S. Forenbaher, Monographs and catalogues, Archaeological Museum of Istria, 14, 455–481. Pula: Archaeological museum of Istria.

Mirosavljević, V. 1955. “Izvještaj o istraživanjima na otocima Lošinju i Cresu 1953. godine.” Ljetopis Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 60: 205–214.

Mirosavljević, V. 1956. “Južno područje otoka Cresa u pretpovijesno doba (Istraživanja 1954. godine).” Ljetopis Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 61: 262–279.

Mirosavljević, V. 1959. “Prethistorijska nalazišta na otocima Lošinju i Cresu.” Ljetopis Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 63: 298–310.

Mirosavljević, V. 1960. “Prethistorijski objekti na otoku Cresu.” Ljetopis Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 64: 204–218.

Mirosavljević, V. 1974. “Gradine i gradinski sistemi u prethistorijsko i protohistorijsko doba. I dio: nalazišta (otoci Cres i Lošinj).” Arheološki radovi i rasprave 7: 259–297.

Mlekuž, D. and M. Črešnar. 2014. “Landscape and identity politics of the Poštela hillfort.” In Studia Praehistorica in Honorem Janez Dular, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 30, edited by S. Tecco-Hvala, 197–211. Ljubljana: Inštitut za arheologijo.

Negroni-Catacchio, N. 1999. “Produzione e commercio dei vaghi d’ambra tipo Tirinto e tipo Allumiere alla luce delle recenti scoperte.” In Protostoria e Storia del “Venetorum Angulus”, Atti del XX Convegno di Studi Etruschi ed Italici, Portogruaro-Quarto D’Altino-Este-Adria 16-19 ottobre 1996, edited by Orazio Paoletti, 241–265. Roma: Istituti editoriali e poligrafici internazionali.

Neiman, F. D. 1997. “Consumption as Wasteful Advertising: a Darwinian Perspective on Spatial Patterns in Classic Maya Terminal Monument Dates.” Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 7 (1): 267–290. doi:10.1525/ap3a.1997.7.1.267

Nora, P. (ed.) 1984. Les lieux de mémoire. T. I. La République. Paris: Gallimard.

Ogburn, D. E. 2006. “Assessing the level of visibility of cultural objects in past landscapes.” Journal of Archaeological Science 33(3): 405–413. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.08.005

O’Grady, R. T. 1984. “Evolutionary Theory and Teleology.” Journal of Theoretical Biology 107: 563–578.

Plourde, A. M. 2008. “The Origins of Prestige Goods as Honest Signals of Skill and Knowledge.” Human Nature 19 (4): 374–388. doi: 10.1007/s12110-008-9050-4

Ruestes, C. 2008. “Social organization and human space in north-eastern Iberia during the third century BC.” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 27 (4): 359–386. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.2008.00314.x

Shang, H. and I. D. Bishop. 2000. “Visual thresholds for detection, recognition and visual impact in landscape settings.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 20 (2): 125–140.

Sirovica, F. 2015. “Pod kod Bruške – analiza nalazišta s osvrtom na problematiku pretpovijesne suhozidne arhitekture / Pod near Bruška – site analysis with a view on prehistoric drywall architecture.” Opuscula archaeologica 37/38 [2013/2014]: 49–93.

Slapšak, B. 1995: “Možnosti študija poselitve v arheologiji.” Arheo: arheološka obvestila 17: 1–90.

Stražičić, N. 1981. Otok Cres: prilog poznavanju geografije naših otoka. Otočki ljetopis Cres – Lošinj 4. Mali Lošinj, Zagreb: Samoupravna interesna zajednica kulture Općine Cres-Lošinj.

Tartaron, T. 2013. Maritime Networks in the Mycenaean World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trigger, B. G. 1990. “Monumental Architecture: A Thermodynamic Explanation of Symbolic Behaviour.” World Archaeology, 22 (2): 119–32. doi:10.1080/00438243.1990.9980135

Veblen, T. 2007. The Theory of the Leisure Class (Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Martha Banta). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Originally published in New York by Macmillan, 1899].

Appendix: site list

No. | Site | Bibliography |

1 | Gornja Glava (?) | Stražičić 1981, 108 |

2 | Petričina | Stražičić 1981, 107 |

3 | Beli | Mirosavljević 1960, 213 |

4 | Halm | Marchesetti 1924, 126; Mirosavljević 1974, 281; id. 1960, 211 |

5 | Sis | Marchesetti 1924, 126; Mirosavljević 1974, 281 |

6 | Velo Gračišće | Stražičić 1981, 107 |

7 | Bartolomej | Marchesetti 1924 127; Mirosavljević 1974, 280; id. 1960, 215 |

8 | Ćule/Pelginja | Marchesetti 1924, 128, 137-139; Mirosavljević 1974, 279; id. 1960, 216 |

9 | Pukonjina | Marchesetti 1924, 128; Mirosavljević 1974, sl. 5 |

10 | Vrh Sela | Stražičić 1981, 108 |

11 | Skulka | Marchesetti 1924 129; Mirosavljević 1974, 279 |

12 | Krasa | Mirosavljević 1960, 212 |

13 | Helm | Marchesetti 1924, 129 |

14 | Ilovica | Mirosavljević 1974, 278 |

15 | Grmov | Marchesetti 1924, 129 |

16 | Kristofor | Mirosavljević 1974, T. VII |

17 | Gračišće | Stražičić 1981, 108 |

18 | Gračišće | Stražičić 1981, 109 |

19 | Vrh Županja | Stražičić 1981, 109 |

20 | Peščenji | Marchesetti 1924, 137 |

21 | Bog/Vela Straža | Marchesetti 1924, 131 |

22 | Osor | Marchesetti 1924, 140ss; Blečić-Kavur 2014 |

23 | Tržić/Bijela Glava | Marchesetti 1924, 131 |

24 | S. Lorenzo | Marchesetti 1924,131 |

25 | Vela Straža | Marchesetti 1924, 131, 134-137; Mirosavljević 1974, 272 |

26 | Halmac | Marchesetti 1924, 131; Mirosavljević 1974, 277 |

27 | Malonderski | Marchesetti 1924, 133; Miletić 2002 |

28 | Pogled | Mirosavljević 1959, 304 |

29 | Maslovnik/Krunica | Mirosavljević 1974, 274 |

30 | Laće | Mirosavljević 1974, 277 |

31 | Brdo | Marchesetti 1924, 113 |

32 | Gradac | Stražičić 1981, 108 |

33 | Kaštel | Miletić 2002 |

34 | Arbit/Turan | Marchesetti 1924, 133; Miletić 2002 |

35 | Polanža | Marchesetti 1924, 131; Mirosavljević 1974, 276 |

36 | Ćunski | Marchesetti 1924, 131; Mirosavljević 1974, sl. 7 |

37 | Osir | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

38 | Grušina | Mirosavljević 1955, 211 |

39 | Vela Straža | Marchesetti 1924, 130; Mirosavljević 1974; id. 1955, 212 |

40 | Stan | Marchesetti 1924, 132; Mirosavljević 1974, sl. 9. |

41 | Krbošćak | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

42 | Tovar | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

43 | (no name) | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

44 | Koludarc | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

45 | Vela Straža | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

46 | S. Martino | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

47 | Kaštel | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

48 | Vršak | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

49 | Piccolo Calvario | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

50 | Umpiljak | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

51 | Stražica | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

52 | M. Telegrafo | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

53 | Bulbin | Marchesetti 1924, 132; Mirosavljević 1955, 209 |

54 | Sv. Ivan/Kalvarija | Marchesetti 1924, 132 |

55 | Garbe | Marchesetti 1924, 133 |

56 | Mulmon | Marchesetti 1924, 132; Mirosavljević 1955, 207 |

57 | Pogled | Marchesetti 1924, 132; Mirosavljević 1974, T. X |

58 | Križine | Marchesetti 1924, 133; Mirosavljević 1956, 264 |

59 | Vela Straža | Marchesetti 1924, 133; Mirosavljević 1955, 206 |

Tables

cca 2200 BC | Early Bronze Age |

1600 BC | Middle Bronze Age |

1200 BC | Late Bronze Age / Istrian Iron Age |

900 BC | Iron Age |

177 BC | Roman period in Istria |

Table 1 Simplified regional chronology

Figures

Figure 2. Prehistoric hillforts of Cres and Lošinj islands (see Appendix for full list).

Figure 4. Approximate sizes of enclosed areas.

Figure 6. Viewshed from Laće hilltop site (radius of analysis: 50 km).