Landscape archaeology is an approach in archaeological research that focuses on space and environment inhabited by past societies. Some would perhaps consider a sub-discipline on its own, situated at the intersection of archaeology and human geography. Unlike traditional archaeology, which often concentrates on specific sites or artefacts, landscape archaeology emphasises the broader spatial context, considering human activities across wide areas. It integrates various methodologies, including remote sensing, geographic information systems (GIS), paleoenvironmental analysis, and traditional excavation, to analyse how landscapes were shaped by humans and vice versa, how human societies adapted to the environment.

Definition and Scope

The landscape can be understood as a cultural artefact on its own. Indeed, heavily laboured agricultural landscapes were shaped to a large extent by human activities, such as rice paddy fields or medieval field systems. That being said, the landscape is not only a physical reality, but also a social and cognitive category. It relates to the known environment and to the means through which such knowledge was maintained. We can think of place names and folklore, as well as the highly intricate bodies of environmental knowledge still maintained by indigenous peoples. In short, landscape is where human lives took place (not houses).

The term “landscape” in landscape archaeology refers to more than just the physical terrain. It includes the cultural, social, and symbolic dimensions of human interactions with their environment. Landscapes are viewed as active spaces that are constantly being modified and reinterpreted by their inhabitants. This approach allows archaeologists to explore questions about settlement patterns, land use, environmental adaptation, and the socio-political organisation of past societies.

Methodological and analytical approaches

A vast array of archaeological methods can be used to understand the inhabited landscape. For instance, specialists in wooden artefacts may produce insights on forest management on the basis of the age and species used as raw material. An archaeological excavation, even when confined to a small trench, can tell us a lot on the wider landscape (food foraging radius, procurement of raw materials, strategic land control, etc.). Nevertheless, there are several methods which were devised specifically for landscape research.

Systematic filed-walking is most commonly organised within a fixed grid of parallel “transects”, where each walker collects and/or records all archaeological data of interest. This highly detailed (and time-consuming) method can produce detailed distribution maps of archaeological sites, features and even individual artefacts. This can reveal the spatial distribution of past human activities across large areas.

Structural survey is focused on visible archaeological features and, traditionally, is undertaken to record architectural remains within their landscape setting. This can be, for instance, a medieval manor within the local field system. Today, the structural survey is undergoing a major revival due to the development and availability of Lidar data. Obtained by air-borne laser scanning, Lidar reveals minute variations in topography, enabling the identification of features such as ditches, banks, stone walls and architecture over hundreds of square kilometres. That being said, desktop analysis of Lidar data does not suffice for archaeological research (even if such statements can be read over the internet). Lidar data is simply computer-screen data, and should normally be verified and examined through field survey, excavation, or other types of fieldwork.

Other remote sensing methods can be equally used for landscape research, such as satellite imagery or thermal sensing. Geophysics, i.e. sub-surface sensing using highly sophisticated equipment can also be used, although such methods are rather difficult to deploy over larger areas (e.g. magnetometry)

Considering the analytical methods, landscape archaeology is naturally coupled with geographical approaches, specifically the GIS. This web site features quite a number of discussions and tutorial on GIS methods, although with a specific focus (visibility analysis, Lidar data analysis). Environmental sciences are also used, such as geology (geomorphology) or pollen analysis. Indeed, pollen grains are remarkably well preserved and abundant – which can inform us on past vegetation. Geomorphological analysis may reveal markers of past soil erosion, which may have been triggered by human activities.

Case Study Examples

1. The Stonehenge Landscape (United Kingdom)

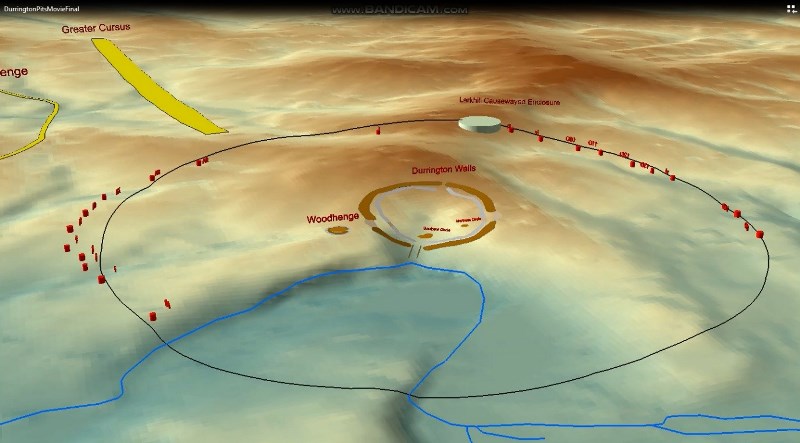

One of the most renowned studies in landscape archaeology is centred on Stonehenge and its surrounding landscape in Wiltshire, England. Researchers have used a combination of geophysical surveys, aerial photography, and GIS to explore the broader ritual landscape around the iconic stone circle. This work has revealed a complex network of monuments, including the nearby Durrington Walls and the cursus monuments, suggesting that Stonehenge was part of a larger, interconnected ritual landscape. The Stonehenge Riverside Project, in particular, has highlighted the importance of the River Avon as a connector between different ceremonial sites, emphasising the role of natural features in the structuring of sacred landscapes.

Key References: Parker Pearson, M., J. Pollard, C. Richards, J. Thomas, C. Tilley & K. Welham (2020). Stonehenge for the Ancestors. Sidestone Press [https://www.sidestone.com/books/stonehenge-for-the-ancestors-part-1].

2. The Maya Lowlands (Mesoamerica)

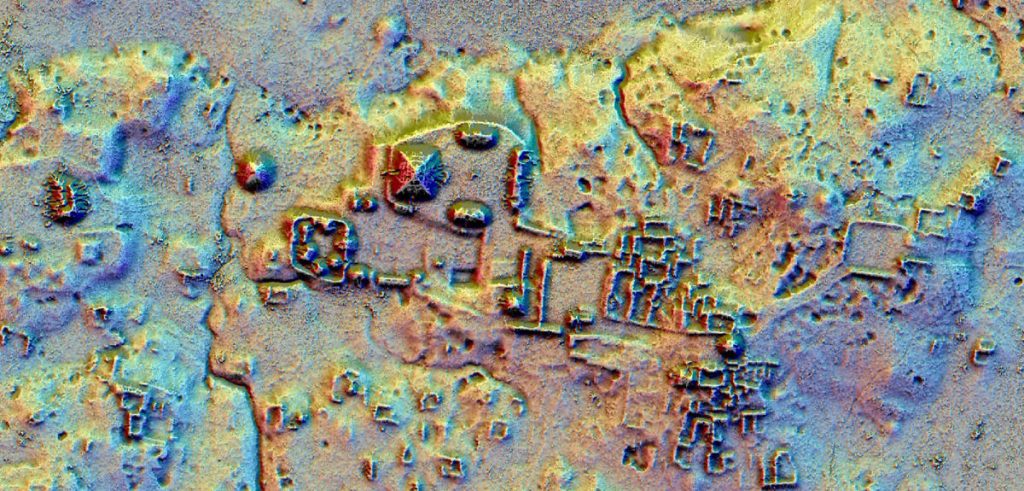

In the Maya Lowlands of Central America, landscape archaeology has provided crucial insights into how the ancient Maya civilisation managed their environment. Researchers have employed LiDAR technology to map vast areas of the dense jungle, uncovering previously unknown settlements, road systems, and agricultural terraces. These findings have revolutionised our understanding of Maya urbanism and land use, revealing a highly interconnected landscape with a complex infrastructure designed to support large populations. The Lidar survey of northern Guatemala, for instance, has shown that the region was much more densely populated than previously thought, with sophisticated water management systems integrated into the landscape.

Key References: Canuto, M. A., et al. (2018). “Ancient lowland Maya complexity as revealed by airborne laser scanning of northern Guatemala.” Science, 361(6409) [https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau0137].

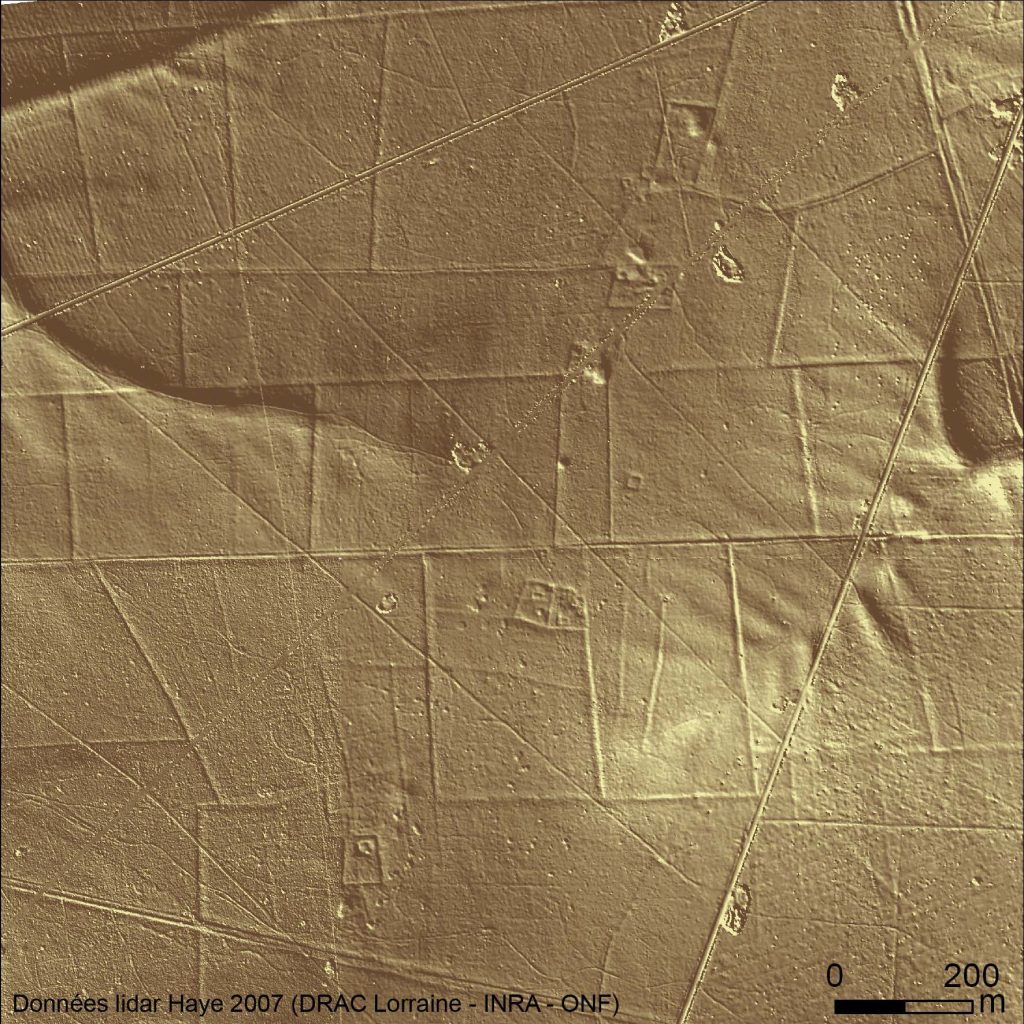

3. Haye forest (France)

The Haye forest, located in northern France, spans some 11,000 hectares and hosts a remarkably preserved traces of Roman filed boundaries and settlements. Low banks and terraces criss-cross the forest and host a number of farms and rural settlements of various shapes and sizes. Elsewhere, such traces have been erased by historical and contemporary land cultivation, but isolated pockets of ancient forests, untouched by heavy agriculture, still survive across Europe and provide a unique glimpse to the past. Due to the excellent state of conservation, the forest was chosen for a detailed Lidar scan, which in turn largely multiplied the quantity of detected archaeological structures. Some 6000 hectares of the Roman countryside have thus been revealed establishing the forest as a key reference for understanding the Roman period agricultural landscape.

Key References: Georges-Leroy, M., J. Bock, E. Dambrine and J.-L. Dupouey (2009). Le massif forestier, objet pertinent pour la recherche archéologique. L’exemple du massif forestier de Haye (Meurthe-et-Moselle). Révue Géographique de l’Est, vol. 49 / 2-3 [https://doi.org/10.4000/rge.1931]

Conclusion

Landscape archaeology offers a holistic approach to understanding the past, emphasising the interconnectedness of people, place, and environment. By examining the broader spatial and environmental context of human activity, it provides insights into how past societies adapted to and modified their surroundings.

This field continues to evolve, driven by advancements in technology and theory – Lidar scaning, paleo-environmental analysis, sensory simulation (sight, sound) -, making it an exciting and dynamic area of research within archaeology. As landscape archaeology progresses, it continues to open new and unexpected insights on the ways we used to inhabit our Earth home.