If anything, archaeologists are much annoyed by messed up chronologies. There are always some “intrusive finds”, “residual artefacts” or “stray objects” that need to be sorted out and removed from the analysis. Archaeological layers almost invariably include small quantities of objects from previous periods that came there either accidentally, for instance when people would dig pits or till the soil, or as “collateral damage” of archaeological excavation and post-excavation work. It is one of archaeologist’s fundamental tasks to clear up this mess and to sort out associations of finds and features (pits, walls, floors etc.) that are broadly contemporary. What we all dream of are neat sequences of archaeological contexts that would line up on temporal scale one after another: settlement phases clearly separated by layers of total destruction, graveyards developing concentrically from the oldest interments in the centre to the most recent on the outer fringe and, more generally, historical periods characterised by exclusive, easily distinguishable types of objects.

So it happens that at some point our cleansing ardour turns into chronological puritanism, a belief that archaeological objects somehow “belong” to singular temporal spans and a practice of slicing up of our subject matter in chronological phases. If objects have singular dates, all we need is to assign them to adequate time-slices. Normally, these dates refer to periods of artefact production/manufacture. Archaeological phases would, then, become associations of objects that were produced contemporaneously, that “belong together” by virtue of chronological mapping. But what about all those objects which clearly do not belong to chronological contexts in which they participate, for instance medieval churches in modern towns or old works of art in museums? Even as remnants of the past, old artefacts are still unavoidable for understanding the functional/cultural contexts in which they remain present.

Time

Holistic or purified approach – the choice is, actually, not that hard for an archaeologist. Our subject matter and our training are invariably organised according to temporal ranges. A medieval archaeologist, a prehistorian: what we do and how we do it is defined by chronologies and not by the historical nature of the studied material.

But, what is the glue which binds these chronological periods together? Note that the key for chronology is not necessarily the function but the origin, the temporal coordinate which is intrinsic to each and every archaeological object. An amphora found in an Iron Age grave in France will always be “Greek amphora” by virtue of its origin, rather than its function(s) (as a grave good, a trading commodity in France etc.). Things are defined by their origin, i.e. their birth time and place.

Time thus becomes indistinguishable from identity of objects, and chronological phases become meta-objects because they describe a unity on a genealogical level. One can, then, proceed to discuss, say, the European Iron Age or the Egyptian Early Dynastic not as an intersection of various historical processes, each with its own dynamics, but rather as a closed system composed of static objects (one object – one date). That is rather convenient, indeed, as one can be a specialist of the Late Iron Age without much knowledge of the Bronze Age or a specialist of the Late Dynastic period without much interest in the Pre-Dynastic. Chronologies are devised for artefact studies, as much as they be devised from the same artefacts…

What is more, many social models that archaeologists use were developed for the contemporary society (19th – 20th century) and are not historical. This applies to landscape archaeology in particular because of its reliance on geographical concepts such as the central place model or site catchment. These approaches are focused primarily on relationships between contemporary processes, rather than their historical developments.

In order to study “historical dynamics,” we need to establish recurring patterns, continuities and discontinuities between already defined and analysed chronological phases. However, this “dynamics” is a secondary phenomenon because the culture itself is entirely contained in time-slices which archaeologist study. Culture is what happens in a time span of, say, 100 or 200 years at maximum, especially if culture is understood as social organisation, i.e. a set of contemporary relationships. In other words, the past becomes something non-cultural, beyond the reach and comprehension of a living society. The past can be considered under same terms as environment, for instance the “historical erosion cycles”, even when these are entirely due to human (past) actions. As if it were a natural phenomenon, the past consists of forces and objects simply existing out there and wielding their innate power.

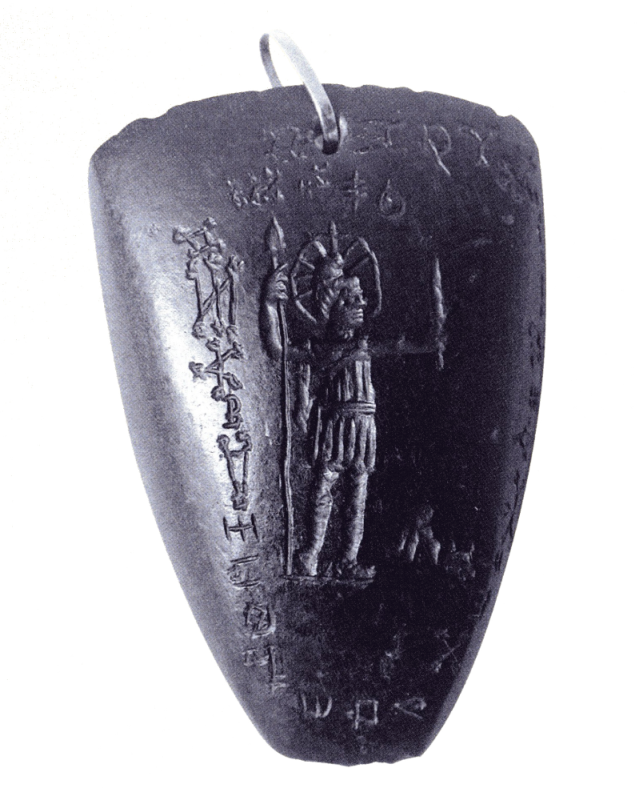

Neolithic axe-head with engraved figure of Saturn and inscriptions in Greek alphabet (Faraone 2014, fig 6; originally from Theocharis 1973, pl. 240)

In sum, anachronistic objects are very annoying, but the problem is not in objects themselves, it is rather in the chronological puritanism. We may “identify” objects by single dates, but their identity is much more complex, much more biographical – and so is the identity of landscapes. A stone axe could have been made in the Neolithic, but it could also have been part of a much later cultural landscape. Romans, for instance, were well aware of stone axes and interpreted them as materialisations of thunder (thunderstones). Archaeologists, however, when stumbling upon such anachronistic association (Roman – Neolithic) usually proclaim that these are a kind of “natural objects”, i.e. curiosities that were interpreted according to contemporary (Roman) systems of meaning – which would then justify the act of purification. Neolithic is not Roman, the object-date paradigm claims. Romans could not have had any notion of Neolithic, they simply (mis)interpreted objects that existed out there. Crucially, this interpretation is entirely Roman, developed within the Roman culture, it is unrelated to the prehistoric Neolithic period and it cannot be an expression of a genuine awareness of such a deep time? But why not?

Historicity

The problem which now emerges is to what extent the (deep) past is a cultural phenomenon, as opposed to a consequence of natural existence of material objects. In other words, how deep could historical awareness penetrate in time and how should we call it, i.e. how should we conceptualise it: as cultural memory, tradition or history? I use here the term historicity, which normally signifies the authenticity of a historical event or a person. In relation to our problem, historicity would be the quality of “pastness” of an object, a quality that emerges at the intersection between object’s intrinsic, non-cultural properties and its subsequent interpretation. It is crucial that this quality is, partly at least, a property of the object itself. For instance, the Neolithic axes became an element of Roman culture because they are found in relatively large numbers and because they somehow resemble actual artefacts, even if they weren’t comparable to anything in contemporary use.

However, small, portable artefacts are generally problematic for the study of “deep” historicity because they can usually be explained away as collected curiosities or otherwise “symbolic behaviour”. Such small finds are normally removed from their original context and inserted into much later one (which is why they capture our attention in the first place). Some curious patterns do appear, however, such as systematic appearance of Neolithic axes in graves (as documented in Scandinavia, for example). A very interesting article has recently been published on the reuse of Neolithic axes in the Roman period (Faraone 2014). Upon closer scrutiny, it can be said that the reuse of these prehistoric artefacts in the form of protective amulets was a generalised practice (ibid).

Turning to cultural landscapes, the choice of a particular site could be related to a particular historicity it carries. For instance, a choice of an ancient site for a necropolis is more likely to be related to particular, site-specific stories, even when these stories belong to an established genre or pattern, such as “Attila’s tomb” that can be found in many places in Europe.

Monumental or otherwise massive constructions, such as megalithic structures of large earthworks often had such appeal, already in prehistory as well as in more recent folklore. These impressive features have a particular, physical impact in the landscape – such sites have to be interpreted somehow, one cannot pretend a large megalithic monument didn’t exist. In other words, their historicity may be unrelated to the actual history of the place itself, but rather to general folklore attributed to such places. The same would be true for remains of large habitats, featuring earthworks, terraces and such.

These examples share a common problem. Both, the Neolithic axes and megalithic monuments come with a natural strangeness, they are obviously unusual, which means that they can always be explained away as natural curiosities. In essence, they are not different than strange rocks or other natural features (cf. Bradley 2000). What I’m interested in is to tease out historicity which is not the property of objects (or not clearly related to them. This is, necessarily, a form of social memory.

What we would need now are sequences of more subtle traces, traces that are not important in themselves but whose biographies rather testify to an awareness their history. A number of such examples can be found in the volume entitled “Memory Myth and Long-term Landscape Inhabitation”, edited by A. Chadwick and C. Gibson (2013), but let me turn to a case from my study area in France.

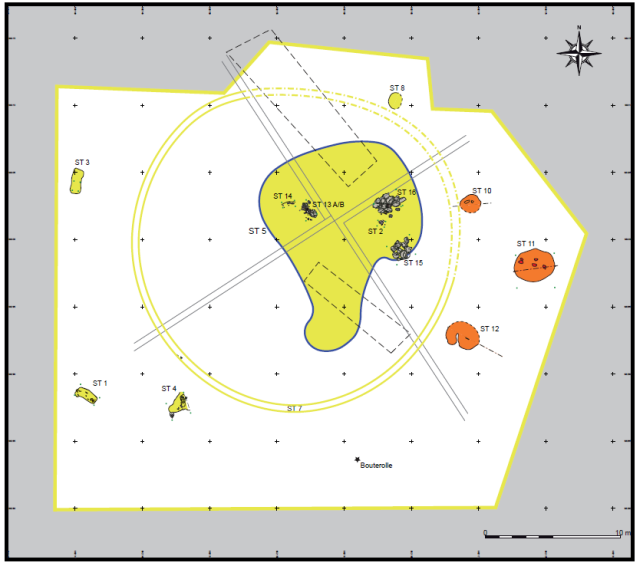

Villemanoche pit (green) (from Chevrier 2012, fig 3).

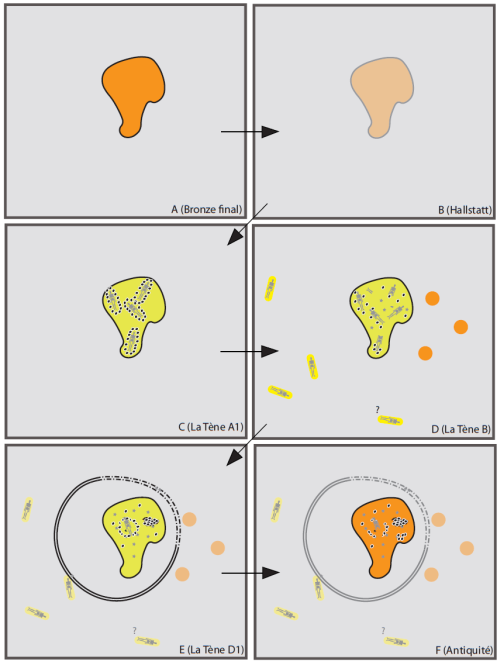

Rescue excavations in Villemanoche near the Seine – Yonne confluence revealed a strange site, rather difficult to characterise. First, in the Bronze Age, a large pit was excavated, presumably for extraction of clay. Such pits are quite typical for the region and can be found on many Bronze and Iron Age sites. Then, possibly some 400 years later, at the beginning of the Late Iron Age, the same pit was reused as a cemetery. Many strange things happened afterwards, including a burial of a horse and a deer with pieces of harness, construction of a circular ditch around the pit and finally possible quarrying for building material in the Roman period. More details can be found in a quite comprehensive article by S. Chevrier et al. 2012). What is interesting for the problem of the historicity of landscape features is that a humble pit, apparently not different from other similar pits in the region, survived in the local memory for several centuries before developing into some kind of “special place”. Of course, the area was inhabited during this time span and the site could have been frequented from time to time. However, these activities did not leave a detectable trace and must have been rather ephemeral. The reuse of the site for cemetery must have been guided by a memory of the place because its presence in the landscape would have been very discrete (a shallow depression at best). This was not a reuse of a ready-made monument such as a megalith or a grave mound.

Perhaps claiming that a place such as Villemanoche pit could have persisted in local memory for several centuries is not such a revolutionary idea, after all. Much deeper time can be discerned in place-names and folk stories in contemporary Europe. However, there is a corollary to this idea that often seems particularly hard to swallow for archaeologists. If previous periods were not present in the landscape only as a collection of material traces, but also through a genuine awareness of the past, that would mean that the “pastness” actually defined some places as such, and more generally that the spatial organisation of a culture reflect that awareness, to a certain degree. This would imply that one cannot study successfully Iron Age graveyards without taking into account what happened and what was remembered from previous periods, including such mundane things as large pits. Worse still, the regional distribution and the appearance of Iron Age graveyards might be closely related to the presence/absence of earlier traces (or even activities without a trace) in the landscape – which would imply that pure historicity becomes a significant factor for understanding the Iron Age. But who would want to go that road?

Sequence of activities in the Villemanoche pit, from domestic use in the Bronze Age through cemetery in the Late Iron Age to possible extraction of construction material in the Roman period (Chevrier 2012, fig. 23).

Bibliography:

R. Bradley: An Archaeology of Natural Places, Routledge, 2000.

A. Chadwick and C. Gibson (eds.) 2013. Memory, Myth and Long-Term Landscape Inhabitation, Oxbow Books

S. Chevrier in collaboration with C. Fossurier, D. Lalaï and J. Wiethold (2014). Des animaux et des hommes inhumés dans une fosse à Villemanoche (Yonne) : un cas particulier de pratiques funéraires au second âge du fer dans le Sénonais. In I. Bede and M. Detante (eds.) Rencontre autour de l’animal en contexte funéraire, Actes de la Rencontre de Saint-Germain-en-Laye des 30 et 31 mars 2012. see on academia.edu

Ch. Faraone 2014. Inscribed Greek Thunderstones as House- and Body-Amulets in Roman

Imperial Times, Kernos 27/2014, 257-284. Available online since October 2016 as http://kernos.revues.org/2283