[This article has been updated and transfered to fragments.hypotheses.org]

Chichibu museum (photo: www.thisiscolossal.com)

Chichibu museum (photo: www.thisiscolossal.com)

Several weeks ago I stumbled upon an amusing article on a museum displaying pebbles and rocks resembling human faces, situated in Chichibu, Japan. The stones are called jinmenseki (珍石) and one should be able to recognise human faces in their naturally occurring dents and holes. The founder of the museum, Shozo Hayama, spent some 50 years collecting these specimens, the only criterion being that human hand did not interfere with the work of nature. There are some 1700 rocks on display, carefully arranged in museum vitrines and sometimes labelled with suggestive interpretations: Elvis Presley, Gorbachev or Donkey Kong. More on the museum can be found in articles listed below.

Chichibu museum (photo: www.thisiscolossal.com)

Chichibu museum (photo: www.thisiscolossal.com)

The word on Chichubu pebble museum spread over the internet through oddities columns, together with museums of torture, toilets, bad art, broken relationships etc. I find that the pebble museum (or Chinsekikan in Japanese, which means “the hall of curious rocks”) open some curious questions for landscape archaeology. After all, the exhibited stones are/were landscape features, created by forces of nature. These are pieces of landscape that were transported to a completely artificial environment. Now, whichever definition of the landscape we prefer, it will necessary refer to values/perceptions/ideas that we happen to find in it or which we happen to project into it. The Chichubu museum is essentially displaying someone’s vision of the landscape (or of nature for that matter), but which is totally shifted. There is no apparent relationship between displayed objects and what they are supposed to look like, but then, what is this quality of “looking like something”?

I -- Simulacra

To begin, let me remind that the “weird pebble issue” is not unknown to archaeology. The oldest such occurrence is the Makapansgat jasperite pebble, a naturally shaped stone resembling a face, discovered in 1925 in the Makapan Valley, South Africa. The site revealed remains of australopithecine (approx. 3 million years BP) who, according to Bednarik (1998), must have picked up the stone at least 30 km away from the site, considering the nearest occurrence of jasperite rocks. No water induced transport (or animal behaviour) would account for the association with human ancestors. The pebble was not used as a tool, neither, considering the absence of use wear and its relatively small size (83 x 70 mm): it seems to be a distant witness of an emerging symbolic mind. There are many other tantalising archaeological finds of that kind (Robert Bednarik published a lot on the problem, cf. below), sometimes called “manuports”, meaning things picked-up but not shaped or otherwise deliberately modified.

Makapansgat pebble http://piclib.nhm.ac.uk

Makapansgat pebble http://piclib.nhm.ac.uk

In any case, my interest here is in fully evolved humans and in the phenomenon of “seeing things” in the landscape, in the strange problem of discourse with natural objects. In other words, we usually conceive of objects as potential carriers of messages whose primary function would be to connect us to a human emitter. Otherwise, objects are just there, without any intrinsic meaning and without any message whatsoever. However, objects do have varying propensities of transmitting certain types of messages because of their shape, size, colour, rarity etc., which means that they do have their share in the discourse. Consider, for instance, the monumentality: it is as much the problem of materials used as of the message itself. As long as intrinsic signals of objects remain in line with the desired message (or at least if they do not distort it beyond a certain point) the communication process is feasible. Sometimes, nevertheless, objects break these boundaries and emit signals which are clearly displaced and which cannot be related to any human emitter. What do I mean by displaced? Signals emitted by objects due to their materiality (eg. colour, shape) do not have the same status as those that we interpret as discursive. Objects, and in particular non-man-made ones, do not have the right to participate in the discourse by themselves, i.e. they do not have the discursive identity, the “I” who speaks. Or do they?

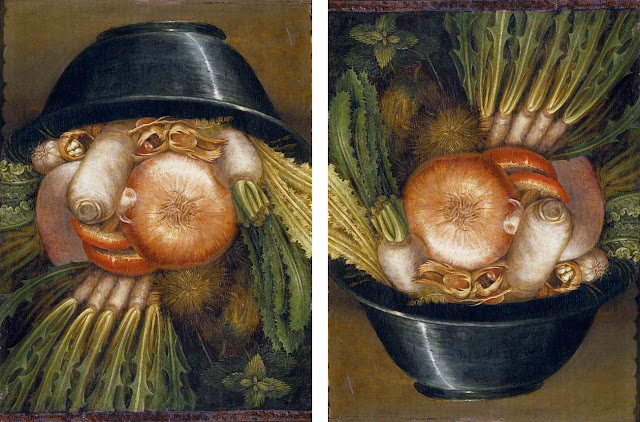

What we are dealing with in the case of pebble faces is the question of simulacra: deceiving signals, images such as Elvis or Jesus in potato chips. It can be approached as a philosophical issue, namely the relationship between representation and reality – but let’s not dig too deep here. On the level of cultural analysis (i.e. “shallower” than philosophy), taste for resemblances and visual metaphors is itself an important topic. Some cultures and some historical periods have developed a particular penchant for “seeing in things”. Michel Foucault (1966) has written quite a bit on the importance of the theory of resemblances for the early modern European thinking about the world (16th century more or less). Observing resemblances was the path to the truth, to an understanding of the world: for instance, a plant can be understood by observing resemblances with an animal – both have their upper and lower parts, a head(s), body/trunk, limbs and a system of veins. In fact, finding resemblances was more like halfway to explanation, the other half consisting in relating all this to the divine order of all things. Lower parts of man, thus animal, thus plant, correspond to the darkness and Hell etc. Such system of thought would allow some kind of discursive identity to enter things, a non-human “I” behind the message (which is not necessarily divine!). Phillipe Descola terms such thinking as analogical, i.e. based on analogies between things as much as on properties of things as such. Cultures of the Far East, China in particular and then Japan, would fit squarely into his “analogical type”, in particular regarding the ways the nature (and by consequence landscapes) was understood in times prior to massive occidental influence.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo 1587-90, The Vegetable Bowl / The Gardener, a “reversible portrait”

Giuseppe Arcimboldo 1587-90, The Vegetable Bowl / The Gardener, a “reversible portrait”

The reference to analogic tradition is certainly important for understanding the pebble museum in Chichubu. A particular relationship with nature survives in Japanese tradition, not only on the level of popular beliefs (kami natural spirits and all that) 1, but also on a more fundamental level of the definition what nature is and where it stands in relation to humans. Nevertheless, the cultural reference does not equal an explanation for the museum: as far as I can tell (not reading Japanese) the museum is an oddity in its homeland. Perhaps the cultural background might account for a certain level of possibility for it appearing in Japan, but no more than that. This would mean that the pebble museum can also be questioned from a more general point of view, namely the one of the landscape as such, regardless of culture.

II -- The mystery of museum

We can pose now two basic questions. First, how could the most banal elements of the landscape – stones and pebbles – enter a museum, a shrine of culture, science and, ultimately, the domination over nature, itself represented as dissected, analysed and explained. We should not forget that specimens in distinguished geological collections are also just that – stones. Science or personal whim, there is always a criterion, there is always a vision. Second, returning to the landscape, we may ask what is it exactly that we may see in it, to what extent does our imagination play upon the idea of landscape, and then, to what extent is our vision (i.e. imagination) influenced by another’s? Does landscape come with attached interpretations, as do museum exhibits?

We could conclude offhandedly that the question of choice criteria is a problem of social environment and/or of personal preference. Sure, there are many books on ways (western) societies constituted an image of their world and of their place in it through museum expositions. In a way, a museum is an ultimate domination over the world; even the scary things lose their power in there. But why bother with museums which are costly and cumbersome institutions, don’t we have creative arts for “self-indulging representation” (literature, film, theatre)? Why investing such amounts of time to objects (including dead humans and animals) if an agenda for their interpretation has already been set elsewhere? Scientists have an opposite point of view, it is our discovery of the world of objects (and objectified living beings) that has many amazing stories to tell, stories that often feature the element of surprise, which is to say the unpredictability of objects themselves. The very idea of discovery gives a role to objects, to their sudden appearance in front of the researcher. In other words, discovery resides in the object as such, even when driven by a specific agenda.

However, regarding the pebble museum, there is a serious problem in the way objects appear to their discoverer. In a “serious” museum, objects enter for what they are; normally, the attached legends do not inform on someone’s imagination, but rather provide a truth-qua-identity claim. “Neolithic axe” and not the face of Tom Jones. Museum is where objects finally disclose their true identity, where we might see them in a rare moment of truth. This is where Mr Hayama enters with his playful ease of setting up totally fake identities of objects. His work only resembles a museum, it is actually an overt parody of the idea because objects appear for what they are not. But anyway, we tend to look at those stones and, what is disturbing, once served with his interpretation we start to realise just how difficult it is to develop our own. A mental image is like an infection, you may or may not resist, but it just doesn’t go away.

Now, the problem is not in the truth vs fake (for scientific truth has a strange habit of changing disguises), but rather in the very fact of looking at the specimens behind the glass – just like in a real museum. Two things make this situation possible: a display of the true identity of objects and the existence of a vision, of a system which is organising the collection. The true identity, the one whose revelation is the fundamental postulate for a museum, is in the case of Chichibu the natural origin of stones. These are all works of nature, untouched by human hand, and that is what we are looking at – natural objects. However, these objects are untamed, unexplained, at least for our modern mind which refuses playful and whimsical analogies. We do not define objects according to completely haphazard resemblances. The second element is an overarching vision, in terms of the selection of objects and in terms of the system of interpretation. Let me be emphatic: in all those faces we see but one – the interpreter, the organiser. Note how in the standard museum the highest virtue of the interpreter is his/hers transparency, he/she is the invisible channel between the visitor and the truth claim attached to the object. But the objects do not speak for themselves, it is rather their labels.

III -- The mystery of landscape

The previous chapter summarised some fundamental problems in the theory of museums, namely the relationship between the identity of objects, truth claims and the interpreter’s agenda – but didn’t I set to write on landscapes? The thing is that the mystery of landscape is the mystery of objects which inhabit it.

Regarding the definition of the landscape, a fundamental distinction has to be made between the everyday space and the landscape as a leisure space. When you drive to work or walk to the nearest bakery, you are not in a landscape, you are fully immersed in a world of objects that have to be dealt with the least possible trouble. Perhaps these places would incite some memories once you move away, but upon actual dealing with the quotidian you just handle the stuff. It is when you make a voyage to, say, Africa that you discover a “desert landscape”. For a local inhabitant, this would still be a simple everyday space, but he/she might perceive your own home as an intriguing landscape. In both of these situations (familiar vs. unfamiliar space) we are surrounded by objects – geographical, natural, constructed etc. – but it is what we see in objects that counts.

Therefore, the landscape cannot be understood as a collection of objects, but rather as the emergence of a discursive relationship or as a revelation of discursive identities of objects. Claiming that topographical setting, vegetation or architecture represent landscape just because of their non-discursive, material existence is not valid. Nor is the term “everyday landscape”. Handling space and objects contained within does not necessarily imply a discursive engagement – if it does, however, discursivity would often come as an afterthought. First I would search for a free bench in a park and then, perhaps, some memories might arrive.

The problem of the discursive identity of (natural) objects is the apparent existence of an “I” who cannot be related to any human. But what about man-made objects? Consider a work of art. The discursive identity of a painting cannot be detached from the concept of the author who is perceived as the “I” behind the “message” (which is so often challenged by contemporary artists). You might refer to the historical epoch, culture or social environment of the artist to distribute the discursive identity among many people, but the principle remains the same: a communication between human beings. On a most fundamental level, a work of art implies a communicative intentionality. Now, no doubt that constructing a house is as intentional as it can get, but the scope of this intentionality regarding the wider landscape is problematic, especially for societies without institutions in charge of urban planning. In everyday dealing with objects in the landscape, there is no evident intention of conveying a message, such as when tilling fields or felling trees. Indeed, the idea of landscape emerged within the learned class of urbanised societies, i.e. those not working the land, first in ancient China and then in Japan and Early Modern Europe (Berque 1995). Note that these are societies with a pronounced taste for visual metaphors and resemblance (cf. supra). The basic requirement for the concept of landscape is a detached observer, someone who is not inside, not dealing with the mess of contained objects, someone who, just like a museum visitor, can see a deeper truth behind the glass.

And now, to close this long story, we can return to Chichibo. If I have compared landscape to a museum, there remains an important problem of curator, i.e. the mediator between the natural and the human worlds. His/her role is to domesticate and to channel the discursive potential of objects in such a way as to align with the underlying vision – which is not to suppress the discursive identity: the objects are still supposed to speak for themselves, even if what they speak is determined by the curator (i.e. the attached label). This is why the museum is such a safe place. However, only exceptionally people would attempt to arrange entire landscapes in a manner of museums, ordering and adjusting everything according to a defined plan (eg. Boboli garden in Florence). Note that I considered curator in terms of vision, imagination, of constructing a worldview, rather than simply arranging objects according to some external agenda. I would say that the main difference between the museum and the landscape lay in the character of custodianship, it being more democratic and less hierarchical considering the latter. In both cases, things are being put under the glass (or in a frame) but the landscape remains quite loosely channelled into a unifying discourse. Chichibu museum can be seen as a (bizarre) reflection of this multiplicity of custodianship over the landscape, of messiness which cannot get aligned with a totalising vision.

The metaphor of curator is a crucial one for landscape archaeology because societies we study (probably) did not have an idea of landscape-behind-glass similar to those of developed societies. It is inevitably us, the contemporary researchers, who establish such a thing as “prehistoric landscape”. However, we can do landscape archaeology if it implies tracing discursive relations of past societies with geographical objects, from pebbles to mountains. These are relations that can be likened to custodianship, i.e. practices of attending to conformity between the land and a worldview. It is only through the figure of the past curator that landscape archaeology might have any meaning and not through endless descriptions and inventories of geographical objects. Otherwise, the term landscape becomes a thin humanistic disguise for geographical/spatial analysis (if it hasn’t already).

Notes

1 « … so far as Japanese people are concerned, deities exist within nature. Even nowadays the deities (kami) are alive and well and quietly thriving. » (Senda 1992, 131)

Charles le Brun cca 1670 (engraving from 1809). “Deux têtes de chat et quatre têtes d’hommes en relation avec le chat.”

Charles le Brun cca 1670 (engraving from 1809). “Deux têtes de chat et quatre têtes d’hommes en relation avec le chat.”

Internet sources on Chichibu museum:

http://www.thisiscolossal.com/2016/11/the-japanese-museum-of-rocks-that-look-like-faces/

http://kotaku.com/wonderfully-odd-japanese-museum-has-face-rocks-1153070477

http://www006.upp.so-net.ne.jp/chinseki/index-ex.html

YouTube :

Bibliography:

Bednarik (R. G.) 1998. The ‘austrolopithecine’ cobble from Makapansgat, South Africa. South African Archaeological Bulletin 53: 4–8. (For other works by Bednarik see: ifrao.academia.edu/RobertBednarik

Berque (A.) 1995. Les raisons du paysage.

Descola (Ph.) 2005. Par-delà nature et culture [translated as Beyond Nature and Culture, 2013].

Foucault (M.) 1966. Les mots et les choses [translated as The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, 1970].

Senda (M.) 1992. Japan’s Traditional View of Nature and Interpretation of Landscape, GeoJournal, Vol. 26, No. 2, History of Geographical Thought (February 1992), pp. 129-134.